Chapter 6 LOGICAL NONSENSE

Americans have such a curiously un-English way of being strictly consistent and logical in their doings.

--Grant Allen (1890)

"You may be right on a technicality."That is how a copy editor—let's call him C—tried to end an argument with me the other day. I was right. And it was technical. It started when C claimed that hung over must be spelled as two words: we put spaces between verbs and adverbial particles like over, so we must put a space in hung over, as we do in other verb + over combinations like flew over. That seems like a logical argument. But a logical argument is only as good as the premises it rests on, and the premise that hung over is a verb phrase is just plain wrong. I threw the evidence at him: if it were a verb, it could change its tense marking. But it can't: the champagne I'm drinking tonight isn't going to hang me over tomorrow. Hungover is an adjective, and so C's argument could not hang together.

C was open to a logical argument when it supported the outcome he wanted: a space in hung over. Once new facts undermined his logic, they were "technicalities"that could be ignored. It reminded me of when people try to end arguments with the accusation "That's just semantics!"I have news for them: semantics is the most important part of any argument. And technicalities are the essence of grammar.

I tell this story because it illustrates how very attached people are to the notion that their way of using English is more logical than other ways of using English—until the logic is tested. If you show that a grammar stickler's premise is incorrect or if you offer an exception to their "logical"rule, you cannot expect to be thanked for that favor. At that point, logic is shoved aside and tradition, precedent, or aesthetics becomes the weapon of choice: "Write it this way because we always have.""Write it this way because that's how it works in Latin.""Write it this way because it looks better."Though their arguments for their preferred phrasing often end with appeals to its alleged age or beauty, language pedants do seem to like to start their arguments with appeals to logic.

The idea that English should be logical really got going with the popular grammarians of the late eighteenth century: Englishman Robert Lowth (1710–87) and American-in-England Lindley Murray (1745–1826) in particular. Rather than following the great writers and speakers as his model for good English, Bishop Robert Lowth's A short introduction to English grammar (1762) dismissed the grammatical ken of everyone from John Milton to the King James Bible. Lowth argued that a double negative makes a positive and that one must say this is she rather than this is her. In other words, he started treating English as if it were mathematics. Negating a negative makes a positive. Two pronouns on either side of is must have the same (nominative) case, just like two numbers on either side of an equals sign must be equivalent.

Lowth's grammar was popular in Britain, but also influential in America, where it was first reprinted in 1775. But Lowth's rules became even more influential because they were imitated by the most successful grammar writer of the early 19th century: Lindley Murray. An American Quaker trained in law, Murray relocated to England after the revolution, hoping (don't ask me why) that the weather in Yorkshire would improve his poor health. He published his 'English Grammar' (1797) for the neighboring girls' school, not intending to publish it further. But it proved too successful to hold back. Republished in the US in 1800, it went through ten editions in that first year alone. Murray repeated Lowth's rules against double negatives, mismatched pronoun case, and prepositions at the ends of sentences, and added more rules, including the ban on singular they. These kinds of regulations, and the ill-applied logics used to argue for them, have plagued English ever since.

English isn't arithmetic, but many people want it to have clear rules like 2 + 2 = 4. Rules themselves are not a problem. The problems come when so-called grammar fans conclude that if one rule is right, then anything else is illogical. That's just not a logical way of thinking. It's like saying that if 1 + 4 = 5, then 1 + 1 + 3 cannot also equal 5. Nevertheless if there are two ways to spell a word or construct a sentence, then people will conclude that one way must be the better way. And our natural egotism means that we're particularly good at coming up with reasons why our own familiar ways of saying or writing things make more sense than less familiar things. That's logic in the sense of Ambrose Bierce's Devil's Dictionary: "the art of thinking and reasoning in strict accordance with the limitations and incapacities of the human misunderstanding.”

But wouldn't it be great if language were logical and maximally efficient? If sentences had only as many syllables as strictly needed? If each word had a single, unique meaning? If there were no homophones, so we'd not be able to mix up dear and deer or two and too? No, absolutely not. No way. Quit even thinking that. What are you, some kind of philistine? If Shakespeare hadn't played with the number of syllables in his sentences, he would not have been able to communicate in iambic pentameter. If words could only have one meaning, we would have to invent a completely new vocabulary every time a new technology came along. Instead of clicking on an icon to open a computer file, you might have to kilk on a zinwang to nepo a wordcomp dak. And if we didn't have homophones, we couldn't have puns. A world without puns! That would be a world without steak puns! And a steak pun is a rare medium well done!

Not only would a logical language be an unpoetic, humorless hassle, it wouldn't be a human language. It wouldn't vary across people and borders like human languages do. British and American English may follow basically the same rules and have the same basic structures, but sometimes the rules are vague and the structures are sketchy, and so they can be applied in different ways. We don't differ on the big things—there isn't a dialect of English that says cat the instead of the cat or one in which cats is the singular and cat is plural. But where the language leaves options open, dialects can differ. Some nouns for places need a the before them and some do not. Which kind of place noun is hospital? The suffix -ed marks a regular past tense, but is learn a regular verb or not? There are rules and patterns, but there are also choices to be made. The fact that we don't make them all the same way is not a crisis of logicality—it's a fascinating aspect of the human condition.

We make the choices we make on these matters because people around us made those choices and we heard them. A dialect is essentially a collection of social habits. We become so used to hearing particular forms that the choices behind them don't feel like choices. When people ask me questions like

· Why do the British (often) say goatee beard when a goatee can't be anything but a beard?

· Why do Americans emphasize the new in New Year (rather than the British style of stressing both words)?

. . . the answer I most often give is: "Because that's how the people around them say it."Whatever historical or linguistic reasons there are for these differences, that's what the answer comes down to. I don't say tarp instead of tarpaulin because (in the words of a charming man on Yahoo Answers) "Americans shorten our language . . . because they only have half a brain.” I say it because that's what my dad calls the thing that he uses as a dust sheet when painting. (And excuse me, Mr. Yahoo Answers: it was not Americans who shortened cardigan, spaghetti bolognese, café, and the BBC into cardie, spag bol, caff, and the Beeb. Plenty of Brits are shortening "your"language.)

We in Anglophone countries may be particularly prone to misunderstandings about how language works; few of us study other languages enough to have any sensible basis of comparison. What grammar we learn in school is often oversimplified to the point of self-contradiction. ("Verbs are action words!"they tell us. "Was is a verb!"they tell us. Can you see the problem?) And so our "logical"justifications for saying things in a particular way are often based on faulty premises. And the faultiest premise of all is: "If it's logical to say it my way, then it must be illogical to say it your way."Objectively speaking, your way of saying something is probably just as weird as anyone else's. It certainly deserves no less explanation than theirs.

The logic of the herd

Unfortunately, or luckily, no language is tyrannically consistent. All grammars leak.

--Edward Sapir, Language (1921)

A sure cure for American Verbal Inferiority Complex is a trip to England. British English sounds much finer when it's filtered through 'Masterpiece Theatre' and BBC America. When Americans are immersed in the full-strength stuff, it smarts. And so it was for this correspondent (let's call her J), who wrote to me after spending some time in London.

American usage is bad enough, but I found British English atrocious, [including] a strong tendency to use singular nouns with the plural form of verbs, e.g., The gang are going to have a tough time protecting their patch and MI5 are looking into terrorist links.

The issue at hand here is what linguists call subject–verb concord: how the number (singular or plural) of the subject of the sentence influences the verb form. In most sentences, a singular subject (←like this one) goes with a singular verb (←like goes back there), and plural subjects (←like this one) go with plural verbs (←like go back there). That seems straightforward, but J's examples have tricky subjects; they refer to singular things (a gang and the British security agency MI5) that are made up of multiple people (gang members, agents). We can think of a gang as being a singular whole, or as being a collection of individuals. That makes gang a collective noun, meaning that it has a singular form but potentially plural meaning.

Now, if you want logic in your language, there are two completely logical approaches to subject–verb concord. The difference between them becomes evident with collective nouns. The first uses grammar logic—it looks at the forms of the words:

· If the subject is in the plural form, use the plural verb form.

· If the subject is in the singular form, use the singular verb form.

The second uses meaning logic, asking what the words represent in the real world:

· If the sentence is about something the group has done as a unit, use a singular verb: The company has gone bankrupt.

· If the sentence describes the individuals in the group doing something as individuals, make a plural verb: The company are giving up their Saturdays for charity work.

In the meaning-logic approach, sometimes both verbs are equally "logical,"since things that a group does as a unit can also be things that the individuals in that group do. So if a band (unit) is playing, then the band (individuals) are playing. The logic thus allows for subtle distinctions, as between My family is big ( 'my family has a lot of people') and My family are big ( 'the members of my family are large'). In the grammar-logic approach, you'd have to say the members of my family or everybody in my family in the second case.

Which of these logics is "better"is a complete matter of taste. As an American, J is accustomed to the grammar-logic approach. In fact, she probably had it drilled into her at school—I know I did. And so she's super judgemental when others don't follow the rule she was taught. What we rarely admit to ourselves is that we don't always follow the logical path we've chosen. Despite American devotion to grammar logic, sometimes Americans peek at the meaning of a singular noun and decide to use a plural verb. A 'Houston Chronicle' article about rappers with Lil in their stage names tells us:

A surprising number are from Houston.

Number is singular; we can tell from that a at the start of the sentence. But if we write A surprising number is from Houston, the wrong meaning comes through. (Which Houston number is surprising? Their area code?) We've peeked at the meaning of number and chosen to make the verb suit the noun's meaning rather than its singular grammatical status. In American, like British, you're also likely to find a plural verb when the subject is at odds with itself, as in the gang hate each other (not the gang hates each other). We also sometimes use singular verbs with plural things. An and should make a noun phrase agree with a plural verb. So we say Clark and Lois are coming to dinner. But then we say Gin and tonic is what they like to drink—treating two nouns as one thing. Despite the best grammar-logic intentions, Americans peek at the meaning and sometimes throw grammar logic out the window.

It's tempting to look at the British use of plural verbs with singular collective nouns and conclude that they're using meaning logic. But they're not, exactly. British grammar guides are pretty honest about it. "No firm rule,"says The Economist Style Guide. "There is no rule,"says Gowers' Plain Words. In this chaos, they advise writers to do their best to approach the matter with sense and a good ear. Even a good ear will have a hard time with British subject–verb concord. The echoes of constant linguistic change make it hard to follow the tune.

The plural verbs struck my American correspondent so forcefully not because they're all she heard in England, but because she only noticed the verbs that were unusual to her. And plural verbs with collective nouns are definitely unusual to Americans. One study showed that Americans use plural verbs after army, association, and public less than 1% of the time in written and spoken English. The respective numbers for written British English were 21%, 10%, and 38%, and for spoken British they were 21%, 50%, and 72%. Singular verbs with collective nouns have been on the rise since the 18th century. Americans moved faster in that direction (no colonial lag there!), but Britons were headed that way too. Until recently.

New research indicates that the British path toward singular verbs (grammar logic) may have reversed in the late 20th century. Perhaps relatedly, whether Britons choose singular or plural verbs seems to have less to do with meaning logic (whether the members of the group are acting independently) and more to do with whether the particular collective noun is one that often occurs with plural verbs. Team is one that seems to attract plural verbs. During the 2016 Olympics, news sources talked about Team GB equally with singular and plural verbs, regardless of whether the team was acting as a single unit or a set of individuals in the particular sentence. For instance, in an article about women's basketball, I read: Team GB are ranked 49th in the world. Grammar logic says that the verb should be singular—and so does meaning logic: the individuals within the team are not each ranked 49th; the team as a whole is. But since British English speakers are now accustomed to hearing about teams with plural verbs, Team GB are just flows off the tongue and into the brain—rankling only those Americans who want grammar logic. The music press is similar: "The The have recently released the soundtrack to Hyena,"The Big Issue tells us, knowing that The The is a band that consists of one musician. Politics gives another set of collective nouns. A British civil servant recalled to me that when he started at the Foreign Office in the 1980s, he was instructed to write 'Her Majesty's government' is, but any foreign government are. In the past decade, though, members of Parliament used are about nine times more than is after the word government. Whether domestic or foreign, the government are plural.

The British reversal of centuries' progress toward singular verbs with collective nouns raises the question: Is this another case like -ize, where British English might be changing course in reaction to American English? Certainly, if any such reaction is happening, it's at a subconscious level. But that's where all the interesting things happen—and logic doesn't live there.

What counts?

E pluribus unum.— 'From many, one.'

--Motto of the United States of America

Singular and plural sound like simple, logical concepts: singular means 'one'; plural means 'more than one.' If only it were so simple. As we've just seen, a team is one singular thing, but sometimes it acts like several plural individuals. If I have a table and a chair, that's two things. Why do we call them furniture rather than furnitures? If a man has had a testicle removed, why can't we say he's lost a gen!tal? Many attempts have been made to find the logic in these things, but they rarely get very far before the rule hits an exception. Some nouns can be easily used as singular or plural, depending on how many things they refer to: chair/chairs, letter/letters, child/children. Other nouns, like furniture, sludge, and joy, tend to stay singular. And others still, like gen!tals, scissors, and leftovers, tend to stay in the plural. Happily, British and American mostly agree on these. Where we don't agree, the odd singulars or plurals can be jarring.

British has a few always-plurals that American doesn't. In the UK, if you can't get your flies closed, you might need to step on the bathroom scales. In the US, if you can't get your fly closed, you might need to step on the bathroom scale. The British plural scales harks back to the old-fashioned kind, on which two things are balanced on a pair of suspended bowls or plates. A scale was one of those suspended bowls; if you put something on a scale, you were putting it on one side of the apparatus. The whole thing was made of two scales. The singular American scale has changed with the times: the bathroom scales of today are self-contained objects with only one surface to put a weight on. Fly went the other way, starting out singular in Britain (mid-1800s) because it referred to a single flap of cloth that concealed a clothing fastener. In the 1950s the British started saying flies—perhaps thinking of the two sides of a zip (or as Americans would say, zipper), rather than the flap of cloth. American English talks of scales and flies as single wholes; British speaks of them as matched pairs. We're counting up the world differently.

English uses its singular form for both individual objects that can be counted (one shark, two sharks) and for masses that can't be counted (water, salt). We can count the sharks in the sea, but we can't calculate how many waters are in the sea. Sharks have nice boundaries. If you have a swimming pool containing five sharks, and you add another shark, the sixth shark remains a distinct shark. Water doesn't work like that; add more water to the pool and it disappears into the water, uncountably. So even when there's lots of water around, it's still singular: water. The basic distinction between countable and non-countable nouns is much fuzzier than those examples make it look. For instance, English treats pasta as a mass noun and noodles as a countable noun, though they're basically the same thing. We eat peas in the plural, but sweetcorn (or as Americans say, corn) in the singular. You can fit about the same number of peas or corn kernels on a plate, but we talk about one as if there are many individual pieces on the plate and the other as if it's just one mass. Most linguists think these things are just arbitrary matters of habit: we learn to treat one as countable and the other as non-countable and we don't think much about it. Others look for deep explanations. At least British and American treat pasta, noodles, peas, and corn grammatically the same. We vary more in how we eat them than in how we say them. (To give one example, Americans are often surprised at the British use of sweetcorn as a pizza topping or sandwich filling.)

Then along come mashed potatoes. Or along comes mashed potato. Americans say it in the plural—the potatoes were countable before they were mashed, and so they stay countable afterwards. Brits look at the mass of finished product and call it mashed potato. This is part of a small pattern: Americans talk of scrambled eggs, which Brits often call scrambled egg. Americans ask if there are onions in the stew; Brits can ask if there's onion in the stew. The British tendency is to think of the inseparable mass in the pot; the American tendency is to think in terms of the countable food before it gets to the pot. Why? Who knows? The situation is easy to describe, but hard to explain.

Lego is an example that drives fans of the building toy bonkers. Americans play with Legos, after which their parents will inevitably step on a Lego then scream bloody murder. Brits play with Lego, then step on a piece of Lego or a Lego brick, then scream blue murder. Proponents of the British singular mass noun often claim that their version is what the Lego company prefers. That's not quite true. Whether mass or count, nouns are a nightmare for companies trying to avoid genericide: the loss of a trademark because it has become an everyday name for a type of product. If you can talk of buying store-brand Legos or own-brand Lego then the Lego company has lost the battle to claim that their name represents only their product. Companies in this predicament insist that these words are not nouns, but proper adjectives. It's not Legos. It's not some Lego. It's the Lego building system. Genericide is not a particularly British or American affliction, but we differ in which companies and products have succumbed. Brits refer to Tannoys, Biros, and Hoovers, which Americans call public address systems, ballpoints, and vacuum cleaners. Americans talk of Kleenex, Band-Aids, and Styrofoam, which the British generically call tissues, plasters, and polystyrene. The British Lego brick is a fine adjective use, in keeping with the corporation's wishes, but British mass-noun use, as in I play with Lego, is no nobler (for intellectual property purposes) than I play with Legos.

Most often, where one country has a singular mass noun and the other has a count noun, it's the British who don't count. Britons play sport, pay tax, provide accommodation, launder bed linen, get toothache. Americans play sports, pay taxes, provide accommodations, launder bed linens, get toothaches. But watch out for one type of count noun that Britons alone use. If an English person says they could murder a Chinese, there is (probably) no reason to call the police. What they mean is that they could devour an order of chow mein or General Tso's chicken. Americans might use Chinese as a mass noun referring to a type of food (Wanna get some Chinese?), but are more likely to use it as an adjective in the phrase Chinese food. And despite their American origins, only the British go for a McDonald's or a Burger King. This fast-food count-noun pattern echoes the established British hot-drink pattern. Americans meet other Americans for coffee. If they want to count how many coffees, they generally add a countable noun, like cup: two cups of coffee. Brits might meet for a coffee. But we all meet for a beer or two after work. The patterns of difference are incomplete and illogical. At the end of the day, when the beer is flowing, we're mostly the same.

Doing the math(s)

[For a Briton to say math] is seen as crossing a red line and going over to the other side. It is an even greater red line than becoming a US citizen.

--William Thomson (2012)

I was taking my very English daughter through the very American experience of Judy Blume books. The books had been bought online in the UK, but as we read 'Otherwise Known as Sheila the Great', I became certain that our copy had been imported from the US. It was full of words like Mom, apartment, elevator, can (of dog food), quart of milk, closet, junior high, and string beans. More usual in a British children's book would be: Mum, flat, lift, tin, two pints of milk, wardrobe, secondary school (which covers US junior and senior high), and runner beans. Although my daughter lives with an American and spends plenty of time in the US, I had to explain some of the basic vocabulary.

But then came maths. Uttered by an eleven-year-old character from New York, that s at the end of maths confirmed beyond doubt the British provenance of the edition. The publishers had been willing to assume that young British readers could make their way past foreign unknowables like cooties (on UK playgrounds, lurgy) and dresser (chest of drawers). But expose youngsters to the Americanism math? God, no. Save the children!

The British stiff upper lip is jolted into a trembling fury by math. Here's a typical online comment on the subject:

It's maths, not math. Look at the long version: mathematics. Math doesn't roll off the toungue [sic] as well with the hard sound at the end.

Please pay respect to this fine ancient subject that is as relevant today as it was with the divine Pythagorean brotherhood and pronounce it nicely.

Maths.

Maths.

Maths.

It's got almost everything you could want in an internet rant. There's bad spelling, appeals to some faraway ideal time, and gaping gaps in common sense. It's just missing the traditional internet-ranting reference to Nazis. "Hey!"I want to yell at this guy. "If we want to pay respect to Pythagoras, shouldn't we say it in Greek? In whose world is 'ths' is easier to say than 'th'? And why would anyone think that the s on the end of mathematics is needed after you abbreviate the word?”

Maybe I should answer that last question. Math. (1847) and maths. (1911) started out as written abbreviations, each with a dot at the end. People originally would have said mathematics when they read them aloud (just as you say "mister"when you read Mr.). But it wasn't long before the very pronounceable abbreviations became words in their own right. Clipping is the linguist's term for making new words by shortening old ones, and English doesn't mind clipping at all. It's how we got lab from laboratory, pub from public house, memo frommemorandum, and exam from examination. The American math is a proper clipping—just the beginning of the word. Just as we have lab and not laby and exam not examn, Americans clip mathematics to math, not maths. The British version is more of a contraction than a clipping, since it includes both the start and end of the word. That's something we do in written language, abbreviating attention as attn. or doctor as Dr. When we read those abbreviations we pronounce the whole word, not the contraction. It's unusual to make new spoken words by using the beginning of a long word plus its last sound. So why keep an -s on maths? Push British English speakers on the matter and you get explanations like this:

Math is an Americanism. In British English, if we seek to abbreviate mathematics, we maintain the plural of the original word and shorten it to maths.

This comes from the well-populated genre of writing guides by people who don't know a lot about language—this one by Simon Heffer. I won't call him a journalist, because he mostly writes opinion, rather than investigation. His two books bemoaning the "corruption"of English are cases in point. If Heffer has the opinion that maths sounds nicer than math, I'm happy to respect that opinion. But whether maths is singular or plural is a matter of grammatical fact, and Heffer has the facts absolutely wrong. Mathematics and maths are not plural in English. I can tell this by reading none other than Simon Heffer, in a column he wrote in 2016:

If one intends to study science at university then maths is invaluable.

Does Heffer think that maths are invaluable? No. Deep down, below his made-up "facts"about language, he knows that maths is singular. Maths is interesting. Maths is sometimes hard. Maths is essential for modern life. Maths is these things. It is a mass noun that happens to have an s on the end. It is not a plural. If it were plural, I'd do two mathematics each day. After my morning mathematic, I might take a walk. In the afternoon, I might choose to do a more difficult mathematic. And when I had finished both my mathematics, I might say: Mathematics are some of my favorite things; I love them. But they aren't. Maths is one of my favorite things. Just one. Singular. I love it.

Elsewhere in the opinion pages, Matthew Engel complains about the cliché do the maths. "I only half-cringe," he writes, "because it still retains its British 's.'"But no s was retained. It was added. The original expression is American: do the math.

Though it does seem to confuse some Brits who think it's plural (while using it as a singular), saying maths causes no problems to the language. It certainly does no harm to mathematics. Six British mathematicians have even managed to win the Fields Medal (the "Nobel prize"of mathematics) despite their extra esses. The s is a harmless flourish. But the insistence that Americans are wrong for saying math: that has to go.

Who wore it shorter?

A great deal of the long-windedness and ambiguity which is creeping into our usage originates in America. Unfortunately, there are many uncritical folk here who think it clever to copy American usage.

--Roxbee Cox, Baron Kings Norton (1979)

Americans are often stereotyped as overdoing things. Guns, teeth whitening, cinnamon—all American habits that British people have asked me to explain "why so much."(Some are easier to explain than others.) And then there's the linguistic version of the "why so much?"question: "Why do Americans insist on putting extra syllables in words?”

The Economist Style Guide warns, "many Americanisms are unnecessarily long."To help you avoid these long Americanisms, they give thirteen examples and their preferable British equivalents. The list includes normalcy and specialty, to be replaced with normality and speciality. Have you noticed? These British "shorter"forms are one syllable longer than their excoriated American counterparts.

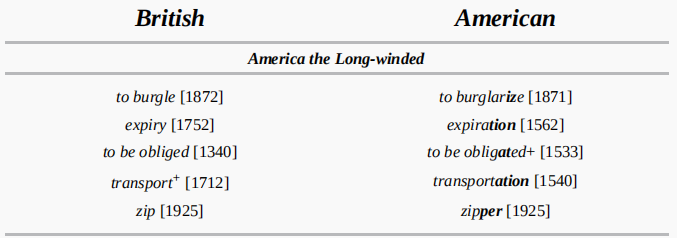

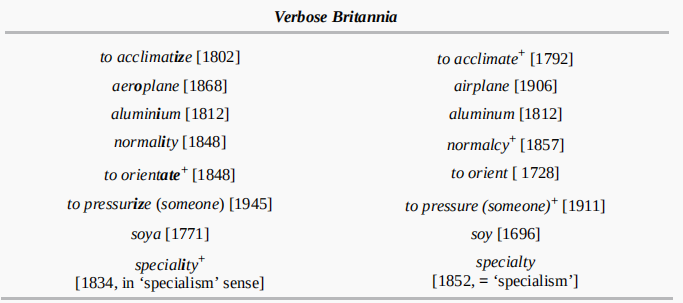

And so it goes. We've already seen that American spellings are shorter than British ones, that British English keeps more of mathematics in its abbreviation, that instead of a short, no-nonsense subjunctive verb form, Brits add a should to give the same meaning. And now some are worried about extra syllables? I'll show you some extra syllables. And I'll include the dates of their first recorded usage so we can see who's adding and who's subtracting.

These are the only examples I've found of "same-ish word, different syllable count"in standard use in the two countries. Rather than America bulking out words with extra syllables, we can see some blatant British syllable addition (acclimatize, aluminium, orientate, pressurize, soya) and American syllable removal: inventing airplane and normalcy and using specialty, a shorter form that had existed in the language (though not with the 'specialism' meaning) since the 1300s.

Sometimes a nationlect has both words in regular use—these are marked in the table with +. Some of these exist as variants within the nationlect with no meaning difference (orient/orientate in the UK, normalcy/normality in the US). But often where there are two forms, there are two meanings. Britain now uses transport for everyday travel because transportation had strong connotations of criminal exile, especially to Australia, in the term penal transportation. Specialty without the i is the correct British word for a medical specialization, but not for a chef's signature dish. Americans may pressure people to do things, but they pressurize their tires. They may obligate you to do things, but are much obliged when you comply.

The two that raise the most hackles are burgl(ariz)e and alumin(i)um. A BBC America article on "Ten American words you'll never hear a British person say"claims that:

While Americans say burglarize, Brits say burgle because it's a crime committed by burglars, not burglarizers.

And that oft-heard reasoning is just as faulty as the oft-heard reasoning on maths. If burglar had come from burgle, then we would spell it burgler, with an e, not an a. The verb burgle is a back-formation from burglar: that is, a word made by removing perceived prefixes or suffixes from another word. (Orientate, from orientation, is another example.) Using burgle for what a burglar does is like saying that vicars like to vic and caterpillars are known to caterpill. Burgle was clearly a joke word when it started out. But faced with burglarize as an American intruder, the British lost their sense of humor and started taking burgle seriously. In the US, burgle still sounds jokey.

Alumin(i)um is known to induce expatriate crises. If I say the American aluminum in Britain, I'm mocked, but I feel silly saying it in the five-syllable British way. So I avoid it altogether: Pass the tinfoil, please. If we want the oldest name, it's the n-less alumium, proposed by Sir Humphrey Davy in 1808. Not satisfied with the sound of it, Sir Humphrey replaced it with aluminum in 1812. Almost immediately, scientists complained that it didn't sound "classical"enough because other element names tended to end in -ium, and so aluminium was born. From then, the -ium version was used in the international scientific community—until 1925, when the American Chemical Society set its standards. As well as dumping the etymologically incorrect sulphur in favor of sulfur, they chose the shorter, older form aluminum. About this event, physicist James Calvert wryly commented: "It is usually the English who have trouble pronouncing more than three syllables in a word, not the colonials.” Looking at how the British pronounce names like Leicester ("Lester”) and how many Brits pronounce words like inventory ("inventry”), it's not a bad observation. At least in the case of alumin(i)um both countries pronounce the word as they spell it.

What the . . .?

The reader is mystified for a moment by the, but soon sees that all he has to do is neglect it.

--H. W. Fowler, A Dictionary of Modern English Usage (1926)

In one of the great Monty Python sketches, the question "What's on the television, then?"is answered with "Looks like a penguin."The joke plays on an ambiguity—the question is about broadcast programming, but the answer is about a stuffed penguin perched on the television set. It is a British ambiguity (though Americans can get it). Americans are much more likely to say on television for the programming meaning than on the television (and nowadays Brits can too). Is this why British humor is so admired? Not the dry wit or the surrealism, but the ambiguous definite articles?

Oh, probably not. But British English does do well on the the front. British women go through the menopause; American women just go through menopause. I have been told that the the is needed because you only do it once. The is a definite article, after all; it's supposed to indicate some kind of uniqueness. But that reasoning is contradicted by puberty: not even the British call it the puberty, even though, like menopause, you only go through it once.

In general, the shows up more in British English than in American. Despite America's greater tendency to use the with some diseases (the flu, the measles, the mumps), British English has more the in other places:

· In time phrases: all the afternoon, on the Tuesday, June the sixth.

· In ways of talking about unusual things: He's the odd type who doesn't like the occasional drink (both instances of the might be an in American).

· In referring to roads, such as in the King's Road or the London Road. The High Street (always with the when talking about it, but not necessarily on the road sign) is the British equivalent of Main Street—a central street with shops.

· In talking about sporting events: one listens to the cricket or watches the tennis.

Americans notice a British lack of the before hospital. In Linguistese, the British in hospital is anarthrous (without an article) and the American in the hospital is arthrous. (I only mention this because anarthrous is one of my favorite words.) Saying it the British way (He is in hospital) makes sense if you consider other anarthrous places like school, prison, and church. The lack of the indicates that we're talking about someone taking a particular role with respect to an institution. If you're in hospital, you're a patient. If you're in school, you're a pupil or student. If you're in prison, you're an inmate. If you go to church, you're a congregant. Nurses, doctors, cleaners, and technicians work in the hospital—only the patients get the the-less phrase.

While school, prison, and church show that the British distinction between in hospital (having a patient role) and in the hospital (being there for any other reason) is part of a pattern, you're far enough into this chapter to guess that it's an irregular pattern. The pattern works for prison, school, church, college, (in the US) summer camp, and (in the UK) university, but not for other institutions. If it were a perfect pattern, then Muslims would go to mosque (which they seem to do in Pakistani English, but not in British or American), the pampered would go to spa, and drinkers would go to pub (which is currently a more robust institution in Britain than any church).

The influence of Gaelic, which has the equivalent of the hospital in such phrases, is probably why it's a bit more common to hear of patients in the hospital in Scotland or Ireland than in England. Some linguists think Gaelic influence is why Americans say the hospital. I am not convinced. Instead, I suspect that hospital is another case like clothing and car parts: Britons and Americans had to devise their own ways of talking about these things because they came pretty late in the development of the language. The first modern hospitals in England (as in, places where people were trying to actually cure disease) were founded in the 1710s, followed by the first American hospital in 1752. The first cases of in hospital don't show up until the mid-19th century, so rather than Americans saying things less like the English, it was the English who were now talking about hospitals in a new way.

The moral of the the story: sometimes the is just a syllable. At other points in English's history, people have studied the Latin and the mathematics, practiced the millinery and the dressmaking, saved things for the posterity, and played the chess. English lost those the's, and it will no doubt lose and gain others.

Why noun when you can verb?

America, with the true instinct of democracy, is determined to give all parts of speech an equal chance.

--Charles Whibley (1908)

Prince Charles has a lot invested in words. As I write this chapter, we still have the Queen's English. But pretty soon it'll be the King's English again. King Charles's English. Taking his inheritance seriously, Charles has asserted that American English is bad because Americans "invent all sorts of new nouns and verbs and make words that shouldn't be."When he's in charge, it seems, Charles will exercise his divine right to decree which words should be. Lexicographers across the land will scurry to effect His Majesty's wishes, lest they be imprisoned in the Tower of London or exiled to the antipodes.

OK, maybe I'm reading too much into his "words that shouldn't be"line. But which words was he talking about? Hardly any words are invented from scratch, so I suspect that Charles meant new words made from old words: the verbed nouns, the nouned verbs, the compounds, the prefixed and the suffixed, the clipped and the blended. Maybe especially those verbed nouns. They're all the rage—that is to say, people rage at them. Simon Heffer urges his fellow Britons to resist "this American habit"of sourcing ingredients and authoring books. During each 21st-century Olympics, the British air has filled with complaints about the "new verbs"medalling (in the US, medaling) and podiuming. Everyone seems to forget that they heard the same complaints four years earlier. If you'll allow me to adjective a noun, the funnest part of these complaints is the unwittingly hypocritical use of verbed nouns. An executive promised that if he ruled the world, he "would outlaw the use of nouns as verbs.” A blogger worries about the "butchering of our language."Maybe they're in on their own jokes using those noun-derived verbs. But they don't seem to laugh much.

According to Heffer, it's clear "from even a cursory encounter with one of that country's television programmes"that Americans are responsible for the verbed nouns. That's his evidence. Was his cursory encounter with an episode of 'How I Met Your Mother?' Maybe Baywatch? I'm going to go out on an academic limb here and say: that's not enough evidence. It's also not hard to get more evidence. To do that, I chose two sections of the Oxford English Dictionary: words starting with ca- and mo-. There I found 464 verbs (not counting those marked obsolete), 220 of which had first been nouns. That's not even counting the verbs, like cannibalize, that were built from a noun and a suffix. In other words, if you want to do away with verbed nouns, you'll have to give up nearly half your verbs.

More than half (112) of those noun-verbs come from before 1800, with peak verbing in the 1500s and 1600s. That's when we got to cake, to carpet, to cane, to camp, to caution, to moan, to mob, to mortgage, to mouth, and many more. My favorite verbed noun from the period is to cater. Originally, a cater was a person who cated, or dressed food. So modern-day caterer is a noun from a verb (to cater) from a noun (cater) from a verb (to cate). Impact, a perennial horror for anti-verbers, is another case like that: a verb meaning 'to press in' became noun meaning 'impression' became verb meaning 'to make an impression.' So verbing nouns is nothing new—and neither is nouning verbs (a long walk, a light drizzle, a good read, when push comes to shove) or making adjectives into verbs (to best, to cool, to short).

Those who complain about "new, American"verbings often concede that the verbs existed before America did (as Heffer had to for to source and to author). But has the flavor or rate of verbing changed in the American era? Benjamin Franklin certainly worried about it. He wrote to Noah Webster in 1789, urging him to speak out against the "awkward and abominable"verbs to notice, to advocate, and to progress. (All of which had been in use in Britain before America was colonized.) Nineteenth-century travelers commented on the American propensity to mail letters, to room with others, and to interview people. All that time, though, the British were making verbs out of nouns too. Of the fifty-two 19th-century verbs in my OED sample, thirty-six are British, including to cab (it somewhere), to catapult, and to motor. The sixteen American ones include to cable ( 'telegraph') and to can ( 'tin').

In the 20th century, 40% of all new verbs in the OED started out as another part of speech. American verbing does speed up in the "American century”—but only to the point that UK and US come to a draw: twenty-eight new verbs each in my OED sample. These include British to caddy and to MOT (pronounced "em-oh-tee”: 'to have or pass the government-required vehicle inspection') and American to camouflage and to monitor. Australians contributed two more: to motorbike and to mozz, 'to jinx,' from the Australian (via Yiddish, I was surprised to learn) phrase to put the mozz on.

Why do Americans get the blame for verbing, then, if the British have been doing it all along? My hypothesis is that verbings cause a bit more mental distress than other new word usages. Our minds are creatures of habit when it comes to processing incoming sentences. If you hear I think we should . . . your brain knows that a verb will soon follow, and so it waits in expectation of that verb. It dims the lights on the mental pathway to nouns and gets the verbs ready for action. If a known noun then shows up, your mind has to scramble to get back on track and find a way to interpret that noun as a verb. After hearing the new noun-verb a few times, you'll get used to it, but for a while you might hang on to the resentment that "somebody else changed my familiar old word and made me work a little harder to understand it."It's an old person's problem. The next generation will live with the new verb all their lives, and so it won't "clang"in their ears and brains. In the 1930s, people were up in arms about the new verb to contact. By the 2000s, we're so used to contacting people that only the nerdiest of language nerds noticed when it was anachronistically uttered on 'Downton Abbey'.

English is susceptible to conversion (the linguistic term for changing a word's part of speech) because our nouns, verbs, and adjectives can look and sound a lot alike. Most English nouns don't bother to wear their nouniness on their sleeves. For a word like camp, anything goes. It sounds like other adjectives (damp), other nouns (lamp), and other verbs (stamp). And so the language doesn't mind if you camp at a camp camp: verb, adjective, noun. But for nouns with suffixes like -tion or -age that say, "I'm a noun,"verbing can seem to go against the grain of the word itself. Though some suffixed nouns end up as verbs (like caution, motion, and position), usually we try to avoid such nouny-sounding verbs. Instead we make back-formations like televise from television and tase from Taser. When the noun suffix stays on, as in the case of leverage, it strikes many people as a very strange verb indeed. Nevertheless it's a fool's errand to take the -age off in order to avoid "verbing." Lever spent nearly six hundred years as a noun before it too became a verb.

The verbed nouns that blend most easily into the linguistic landscape are those that express a concrete meaning that newly needs expressing: to skateboard, to google, to pepper-spray. The ones that have most annoyed are those that express more abstract actions: to leverage, to action, to broker. Being abstract means that more of an argument can be had about what the verbs mean and whether their meanings could be expressed with old verbs. These verbs are associated with the hated business-speak, which also gives verbing an American sheen (as we saw in chapter 2), whether deserved or not. The businessy verbed nouns that British newspapers complain about are as likely to be British as American. "This will anniversary as we move into the first quarter of 2011,"reads one British department store's market report, while another says, "better-balanced autumn ranges should allow M&S to anniversary tougher comparisons.” Um, it has something to do with years . . . I'm not sure. They haven't verbed that noun yet where I come from.

People like Simon Heffer who complain about verbing are often concerned that the new verbs "shunt perfectly serviceable ones out of the way and into desuetude.” That misses the point of why those nouns became verbs in the first place: not to replace another verb, but to replace a more long-winded expression containing the noun. To interview wasn't dreamed up to replace to talk with, but to be more efficient than to have an interview with. People are tasked with doing things because that's shorter than giving someone the task of doing something. Caddy is shorter than serve as a caddy for, motorbike is shorter than travel by motorbike. No existing words were harmed in creating this efficiency.

It's not just noun-to-verb conversion that bothers people. "The American obsession with the prepositional verb is notorious,"gossips the first BBC News style guide (1967). I have to say, obsession seems a much better word for the British reactions to these American forms. Visit with "should be made unwelcome,"says 'The Complete Plain Words'. To head up a committee is "vulgar,"declares Simon Heffer, and for John Humphrys meet with embodies "the obesity of our language.” These British complainers quickly conclude that since they don't use those prepositions, the prepositions must be unnecessary. Their diagnosis of redundancy reveals a dispiriting shortfall in curiosity about the language. They have not made any effort to notice that the prepositions clarify and add nuance in American English.

In the case of meet, American English is fighting ambiguity. Usually, language tolerates words with multiple meanings pretty well. The context will sort out for us that broke means something different in I broke my toe and I broke a world record. But for meet, the context often leaves a lot of possibilities open. I met the mayor before the ceremony could mean:

a. I made the mayor's acquaintance before the ceremony started.

b. I encountered the mayor on the way to the ceremony (and perhaps we exchanged pleasantries).

c. I went to a place at a predetermined time in order to see the mayor.

d. The mayor and I sat down and had a meeting prior to the ceremony.

American English rebels against this ambiguity, and it does so with prepositions. The 'encounter' meaning (b) has mostly been replaced by run into. (That one has proved so useful that Brits are saying it too.) The 'rendezvous' meaning (c) gets an up: The mayor and I met up or I met up with the mayor. The 'have a meeting' sense (d) has been taken over by meet with. Now that all of those meanings have their own expressions, the default way for Americans to interpret I met the mayor is the (a) sense, 'make the acquaintance of.' For British English speakers who don't use these prepositions, the listener (or reader) has to do more work (if they can be bothered) to determine which kind of meeting activity went on.

Other phrasal verbs add other nuances. Visit with involves sitting down with someone and having a conversation. That's different from visiting. I could visit an unconscious person in (the) hospital, but I couldn't visit with them. Add up (an adverbial particle, really, rather than a preposition) after a verb and the action becomes more active and complete. He could head the committee as a matter of ceremony, but if he heads it up, he's invested in the process.

When British usage gurus aren't complaining about added prepositions in American English, they find time to complain about missing ones. They say that protest is "incorrect for protest against"and that one should not (Americanly) appeal a verdict but instead should appeal against it. Here I have to note that not every preposition adds more meaning—some are just a matter of linguistic habit. We listen to music, but if we were to decide tomorrow to drop the to and listen music, we'd have little choice but to interpret it the same way. The same is arguably true of appeal against—if there's no meaning difference between appeal against the verdict and appeal the verdict, then the preposition is a matter of tradition and window dressing, not meaning.

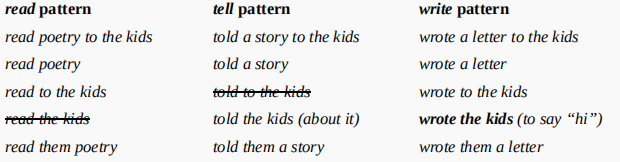

More British pedantic consternation is inspired by the American ability to say things like I wrote the company to complain, where Brits must write to the company (and Americans can as well). American English lets write follow the same pattern as read or tell, but British English makes write follow only the same pattern as read. (The bold one is normal in American English only.)

There's no logical reason why write shouldn't follow the tell pattern. They are both verbs about transferring information through language, which means they both need to be arranged with other phrases that describe a communicator, a recipient of the communication, and something that's communicated. The people who object to write the kids do so because it's not what they're used to hearing. It's not an approved convention for using the verb write in their nationlect. Fair enough. If it's not part of your nationlect, you don't need to say it. That doesn't make it wrong to say. It's just not yours to say.

Can I get some logic here?

It infuriates me. It's not New York. It's not the 90s. You're not in Central Perk with the rest of the Friends. Really.

Steve of Rossdale, Lancashire

Can I get a coffee? This simple question tops many a British list of annoying Americanisms. When it does, it's not long before someone (like Steve) claims it's "straight out of an old Friends episode.” Is it possible that one sitcom is responsible for one of Britain's most common and complained-about ways of ordering food and drink? Let's look at the evidence. Can I (or we) get is used in 30 requests in the 236 episodes of Friends. Considering that Friends was on UK televisions nearly nonstop during the '00s, often with four episodes per day, that means the phrase probably showed up on British televisions every other day for about seven years. Maybe that, paired with the simultaneous boom in American coffee chains in the UK, was enough to do it. But to blame an American sitcom for Can I get a coffee? is to ignore the glaring Britishism in the question: referring to a cup of coffee as a coffee. Except for one instance each of a coffee to go and a decaf, the Friends ask for some coffee or some cappuccino or a cup of coffee. The Britishism a coffee was just making its way into American English at about the same time as can I get was entering Britain.

After blaming Friends, British can-I-get grumblers launch their logic against the question. No, you cannot get a cup of coffee, says a Louisa C. in the Mail on Sunday, "unless you are planning to clamber over the counter and start fiddling with the steam spouts.” But interpreting get as only meaning 'work to obtain' is just pure stubbornness. Louisa and her compatriots use get to mean 'receive' in all sorts of contexts, so it's not a long jump to understand it as meaning 'receive' in the ordering-coffee context. In fact, one of the most frequent (and pre-Friends) uses of can I get in Britain is Can I get a copy of this? The askers of that question are rarely asking 'Can I take over your copy machine?' or 'Can I write out this text?' They mean 'Would you give me a copy of this?' or 'Can I receive a copy of this from you?' The British get refunds and get birthday presents, so the 'receive' sense of get is alive and well. All that's changed is that it's now heard in coffee-shop questions.

The appeal to logic is a distraction tactic. The real reason can I get sounds bad in Britain is because it's not the way British folk have been taught to make a polite request. Being polite (especially in Britain) is largely a matter of saying words that are routinely associated with being polite. For Brits, Can I have a coffee? works as a polite request. It works less well for Americans, for whom it can sound like asking permission to have coffee, rather than asking to be given coffee. For people without can I get in their repertoire of polite-request forms, the get can sound a bit rude. They then want to explain to other people why they shouldn't say can I get, and they get tripped up by trying to apply logic to the situation.

I can't help but think, though, that can I get was doomed to complaint from the start because get is the runt of the English verb litter. People hate this useful 12th-century Viking gift to English. Kingsley Amis recalled that at his school get and got

were suspect words, not exactly erroneous in themselves but vulgar. I'll get it or he's got it were said to be expressions lazy/stupid people fell back on because they were too stupid/lazy to think of or to know genteel words like obtain or possess. Even today both get and got retain a whiff of informality, so they should be avoided in solemn contexts or when trying to impress an octogenarian.

Robert Burchfield's teachers similarly left him "wondering if get could ever be used in an acceptable manner."Even after growing up to write the third edition of Fowler's Modern English Usage, Burchfield seemed no more confident on this point. Other style guides, from Gowers' Plain Words (1954) to Garner's Modern English Usage (2016), reassure us that get and got are perfectly good English and that we should not fear using them. But those style guides have to keep repeating that message because we English speakers are just not so sure.

Get avoidance is probably why Americans started preferring to say I have (a job or a husband or a pineapple) and why Britons did not complain when that particular Americanism started taking over the more traditional British English I've got. Whatever matters of taste keep people from wanting to say get and got (not to mention gotten), it remains one of the most useful words in English—with dozens of different applications, including many that were invented in the US and have since spread to the UK, like:

· 'to answer': Get the door, would you?

· 'to bother': What gets me is the price.

· 'to best in an argument': You've got me there.

No need to fret about get. As Anthony Burgess once demonstrated, you can just relax and use it all day:

I get up in the morning, get a bath and a shave, get dressed, get my breakfast, get into the car, get to the office, get down to work, get some coffee at eleven, get lunch at one, get back, get angry, get tired, get home, get into a fight with my wife, get to bed.

Let the logic go

When dealing with people, remember you are not dealing with creatures of logic, but with creatures bristling with prejudice and motivated by pride and vanity.

--Dale Carnegie, How to Win Friends and Influence People (1936)

Logical languages are good for computer coding, but they stymie human communication. We're not robots. We're poets. Every day we have new things to talk about. Every day we're building relationships with other people. And every day we find new ways to do these things using the raw materials of English. And English lets us, because it is a fantastically flexible medium in which to create things.

The extent of English's flexibility was brought home to me early in my linguistics training. The professor assigned our class to find ten examples of a particular word out in the world and then try to find the meaning of each instance of the word in a dictionary. Anyone who could find all the meanings probably hadn't looked carefully enough at how the words were used. It's impossible for a dictionary to represent the full extent of how we use words because they change—or rather we change them—constantly. Think of the word table. In I put a table in my painting, it doesn't mean 'table'; it means 'image of a table rendered in paint.' In The whole table wants beer it means 'group of people sitting at a table.' When a priest says Everyone is welcome at our table, he might well mean 'our church' or 'our community.' Often when we say table we only mean the 'upward-facing surface of the table,' as in Clear the table or Put flowers on the table. We rarely bat an eye (or an ear) at such specific uses of the word. On a daily basis, we wring new meanings (some that might only be used once) out of the words we know. On a daily basis, we combine words into phrases that have never before been said. And yet we (mostly) communicate well. There is no need for alarm. There's need for wonder. We are fantastic communicators, and so is English.

So if someone tells you that a word cannot mean X because it already means Y or that we should all stop saying Z because it is logically inconsistent, just say to yourself: here is a person who doesn't have a very good sense of how English works. If you want to entertain yourself, you can point out the inconsistencies of their argument. If you want an easy life, you can just ignore them—up to a point. If you see that person spinning their illogical yarns in front of a classroom or a government education department, you have a moral duty to step in.