Designing Your Life:

How to Build a Well-Lived, Joyful Life

by Bill Burnett, Dave Evans

10. Failure Immunity

Imagine there was a vaccine that could prevent you from ever failing. Just one tiny shot, and your life would be guaranteed to go exactly as planned—nothing but smooth sailing and success after success, as far as your eye could see. An entire life without failure sounds pretty good, doesn't it? No disappointment, no setbacks, no trouble, and no loss or grief seems like a fine way to live to most of us. Nobody likes failure. It feels terrible—that horrible sinking sensation in the pit of your stomach, the heavy weight of defeat that can make your chest feel like it's being crushed.

Who doesn't want to be immune to failure?

Unfortunately, there's no vaccine, and it's impossible never to fail. But it is possible to be immune from failure. We don't mean you'll be able to avoid the experience of having things not work out the way you hoped for; but you can become immune to the large majority of negative feelings of failure that burden your life needlessly. If you use the ideas and tools that we've been talking about so far, you will reduce your so-called failure rate, which is great, but we're after something much more valuable than just failure reduction. We're after failure immunity.

We've been trying a lot of different things on the way to designing a life that is worth the living. Using the curiosity mind-set, we've gone out into the world and met some interesting people. We've radically collaborated with friends and family and prototyped some meaningful engagements with the world. And throughout this life design journey, we've gotten comfortable with the bias-to-action mind-set, and whenever we're in doubt, we know it's time to do something.

All along, you have been developing something positive psychologists like Angela Duckworth call perseverance or grit.1 Duckworth's studies on grit and self-control demonstrate that grit is a better measure of potential success than IQ. Failure immunity gives you grit to spare.

It's important to think of ourselves as life designers who are curious and action-oriented, and who like to make prototypes and “build our way forward” into the future. But when you take this approach to designing your life, you are going to experience failure. In fact, you are going to “fail by design” more with this approach than with any other. So it's important to understand what “failure” means in our process, and how to achieve what we call failure immunity.

The fear of failure looms so large in people's experience of their lives. It seems to relate to a fundamental perception in the way people define a good or a bad life. She was a success (yay, good!). He was a failure (boo, bad!). When you look at it that way, no one wants to be a failure. We imagine that at our funerals there will be some external judge (or some imagined life tenure committee) who will pass judgment on whether we managed to succeed or ended up failing.

Fortunately, if you're designing your life, you can't be a failure. You may experience some prototypes and engagements that don't attain their goals (that “fail”), but remember, those were designed so you could learn some things. Once you become a life designing person and are living the ongoing creative process of life design, you can't fail; you can only be making progress and learning from the different kinds of experiences that failure and success both have to offer.

Infinite Failure

We trust that you now understand that prototyping to design your life is a great way to succeed sooner (in the big, important things) by failing more often (at the small, low-exposure learning experiences). Once you've done this prototype-iteration cycle a number of times, you will really begin to enjoy the process of learning via the prototype encounters that other people might call failure. As an example, one day just before our large Designing Your Life class started, Dave made a big change to one of the teaching exercises for that day's class. He had an idea and just wanted to try something out. He didn't even have time to tell Bill, so Bill heard it at the same time as the students did. After Dave announced the (never before attempted) exercise and the students were working on it, Bill came over to Dave and said, “This is great! I love that you are willing to fail miserably in front of eighty students! I have no idea if this exercise is going to work, but I love how you're prototyping it!” Dave and Bill have come to trust the process of life design so completely that they don't ever have a conversation about the right way to run their classes. When you really get the hang of the design thinking approach, you end up thinking differently about everything.

This is the first level of failure immunity—using a bias to action, failing fast, and being so clear on the learning value of a failure that the sting disappears (and, of course, you learn from the failure quickly and incorporate improvements). By the way, that exercise in class went pretty well, and then we decided to jettison it anyway and keep the prior version of the exercise because it was more effective. What a success!

There's a whole other level of failure immunity that we call big failure immunity, which comes from understanding the really big reframe in design thinking. Are you ready? Designing your life is actually what life is, because life is a process, not an outcome.

If you can get that, you've got it all.

Dysfunctional Belief: We judge our life by the outcome.

Reframe: Life is a process, not an outcome.

We are always growing from the present into the future, and therefore always changing. With each change comes a new design. Life is not an outcome; it's more like a dance. Life design is just a really good set of dance moves. Life is never done (until it is), and life design is never done (until you're done).

The philosopher James Carse wrote an interesting book called Finite and Infinite Games.2 In it he asserts that just about everything we do in life is either a finite game, one in which we play by the rules in order to win—or an infinite game, one in which we play with the rules for the joy of getting to keep playing. Getting an A in chemistry is a finite game. Learning how the world is put together and how you fit in it is an infinite game. Coaching your son to win the spelling bee is a finite game. Having your son come to trust that you love him unconditionally is an infinite game. Life is full of both kinds of games. (By games we don't mean something trivial or childish. In this context, it simply means how we act in the world and what importance we place on our actions.) Everyone is playing both finite and infinite games all the time. One kind is not better than the other. Baseball is a great game to play, but it doesn't work without rules and winners and losers. Love is an infinite game—when played well, it goes on forever, and everyone plays to keep it going.

So what does this have to do with life design? Just this: when you remember that you are always playing the infinite game of becoming more and more yourself and designing how to express the amazingness of you into the world, you can't fail. With the infinite-game mind-set, you are not just adept at failure reduction—you are truly failure-immune. Sure, you'll experience pain and loss or serious setbacks, but they won't make you less of a person, and you don't experience these setbacks as an existential “failure” from which you can't recover.

Being and Doing

For millennia, people have struggled with the difficulty of balancing our focus on ourselves as human beings (which is more prevalent in Eastern cultures) or as human doings (which is more prevalent in Western cultures). Being or doing? The real inner me, or the busy, successful outer me? Which is it? Life design thinks that's a false dichotomy. Since life is a wicked problem that we never “solve,” we just focus on getting better at living our lives by building our way forward. This diagram is, we think, a better way to imagine the process:

Cycle of Become=>Be=>Do=>Become

When designing your life, you start with who you are (chapters 1, 2, and 3). Then you have lots of ideas (rather than wait and wait to have the idea of the century) and you try things out by doing them (chapters 4, 5, and 6), and then you make the best choice you can (chapter 8). As you do all this, including making choices that set you on one path for a number of years, you grow various aspects of your personality and identity that are nurtured and called upon by those experiences—you become more yourself. In this way, you energize a very productive cycle of growth, naturally evolving from being, to doing, to becoming. Then it all repeats, as the more-like-you version of you (your new being) takes the next step of doing, and so it goes.

All of life's chapters—both the wonderfully victorious and the painfully difficult and disappointing—keep this growth cycle going if we have the right mind-set. In this way of seeing and experiencing things, you're always succeeding at the infinite game of discovering and engaging your own life in the world.

And that mind-set is a great big dose of our version of the failure immunity vaccine.

Dysfunctional Belief: Life is a finite game, with winners and losers.

Reframe: Life is an infinite game, with no winners or losers.

Now, you may be thinking that this sounds good, but in the real world it's just not so simple. We do believe (and we've seen it in others and lived it ourselves) that you really can reframe failures in such a way that you transform setbacks and have a happier, more fulfilling life. This isn't just our own rehash of positive thinking; it's a design tool that's imperative to life design.

Failure is just the raw material of success. We all screw up; we all have weaknesses; we all have growing pains. And we all have at least one story in us of an occasion when we've reframed a particular failure, where we've changed our perspective, and have seen how a failure turned out to be the best thing that ever happened.

We all have our stories of redemption. A perfectly planned life that never surprises you or challenges you or tests you is a perfectly boring life, not a well-designed life.

Embrace the flaws, the weaknesses, the major screwups, and all the things that happened over which you had no control. They are what make life worth living and worth designing.

Just ask Reed.

Winning and Losing and Winning

Reed always wanted to be a class officer at school, so he started running for office as soon as he could, in fifth grade. He lost. He ran in sixth grade—and lost again. He ran for office every year, often twice a year, and lost every single time. By the end of his junior year of high school, he'd run for one school office or another and lost thirteen times in a row. During his last year of high school, he decided to run one more time—for senior class president.

Over the years, Reed's parents watched with agony as the losses mounted up. After four or five losses, they would wince every time Reed announced, “I'm going to run again!” They were smart enough not to discourage him, but inside they wished he'd just let it go and stop the bleeding. They couldn't stand to see him going through all those failures. But Reed didn't mind. Oh sure, he hated losing—but he wasn't changing his mind. He knew that if he kept at, it he'd learn what he was doing wrong and eventually he'd win—or at least he'd learn a bit more. In his mind, failure was just part of the process. With each successive loss, losing got less painful, which allowed him to take risks to see if new approaches would work. It gave him the courage to try out for other things—sports, acting. Most of these didn't pan out, but a couple did. Though he was delighted with his successes, he would have been just fine even if he'd failed at those, too. Failing over and over freed him to focus his energies on running the best campaigns he could. Each failure was a lesson, so when he ran, he never worried about losing. When he finally won and became senior class president, he was thrilled, but the point isn't that he finally won—the point is how he kept running.

It turned out to be a more important lesson than he realized.

At twenty-two, to anyone who looked at him from the outside, Reed seemed finally to be winning at life. Boy Scout. Class president. Quarterback. Ivy League. Crew champion. When he graduated from college with a degree in economics, his life seemed set on a straight course for success followed by more success. He landed a job with a top firm and for the first few years, his new career was going great.

His job took him on the road often, and during a business trip to the Midwest, Reed noticed a strange lump just below his neck. He went to a clinic during his lunch break to check it out, and by the time he boarded his flight home three days later, a doctor has confirmed his worst fears: Hodgkin's disease, a cancer of the lymph nodes. When he got home, he immediately began chemotherapy.

Cancer at twenty-five was not part of Reed's life design. But it was now part of his life.

A lifetime of experience dealing with failure had paid off. Pretty quickly, Reed was able to accept the reality of his situation and put all his energies into getting better. He didn't get stuck asking, “Why me?” Nor did he believe he had failed at being healthy. He was too busy getting another campaign prepared—this time, a campaign to beat cancer—and then using it. For the next year, he wasn't advancing his economic consulting career, as he had planned; he was undergoing surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy. He was also learning, at a very young age, just how fragile life is.

When his cancer treatment was over and his cancer was in remission, Reed had no idea what to do next. Actually, he had one idea—one somewhat crazy idea. There was this little item on his Odyssey Plan that he hadn't begun to prototype: taking a year off from everything and being a ski bum. He was conflicted. An all-American boy on the fast track to success just doesn't take a year off to become a ski bum and get nothing done.

Reed, however, was not your average Boy Scout any longer. He had just fought a war with cancer, and even though he knew the smart plan was to go back to building his career, and he worried that an additional year of employment gap might ruin his résumé and therefore ruin his life, Reed decided he wanted to live his life, not just plan it.

He did some prototype conversations with businesspeople before he made his decision, because he wanted to learn how future hiring managers might look at that decision, and concluded that he could afford the risk, and that the kind of people he'd want to work with would view his post-cancer ski adventure as a demonstration of boldness rather than irresponsibility. As for how other people would see it—well, that was their problem. The point isn't primarily that Reed “succeeded in beating cancer,” but that he was able to enjoy failure immunity during the process, which enabled him to direct his energy productively and to learn things he could use later. By turning his problem into an advantage, he was able to design the best life possible in the face of adversity. It beats the hell out of being despondently confused about why bad things happen.

The failure immunity he began learning in the fifth grade just kept coming in handy. A few years later, Reed decided to go for his dream job—working for a professional sports franchise, in particular an NFL team. Though he didn't have any family connections in that world, he had met an up-and-coming NFL executive while in college and had been slowly building a network into the sports world through prototype conversations. He made some overtures into the industry, looking for work. The worst thing that could happen was being rejected, but with rejection no longer scary to him, why not at least try?

When his attempts at an NFL job failed, he let go and quickly redirected his efforts into his next, alternative plan.

Over a year later, he finally got a chance to apply for a job negotiating player contracts for an NFL team. Up against dozens of other candidates, many of whom had industry experience, he made it down to the final two and lost—he didn't get the job. It really hurt, but, again, he quickly redirected his efforts into an alternative plan, and he got a job in financial management, working for a great company.

But he didn't give up on the pro team. Despite being rejected, he kept prototyping that career. He stayed in touch with the NFL executives and spent hundreds of hours building innovative sports analysis models, which he would show them every now and then. This was not the usual behavior of people who lost a job. And, yes, he was eventually hired by that same NFL team, for a better job than the one he had originally tried for.

He had worked there for about three years when he decided that pro sports wasn't really where he wanted to be—he “failed” again. So he moved on to a health-care start-up, secure in the knowledge that, if that didn't work out, the next thing—or, barring that, the thing after that—would.

Reed is now completely failure-immune. He's not protected from the personal pain and loss of failure, but he's immune from being misinformed by failure—he doesn't ever believe that he is a failure or that failure defines him, or, in fact, that his failures were failures. His failures educate him in just the same way that his successes do. He likes success better, but he'll take whatever he gets and just keep failing his way forward.

To meet Reed today is to meet what appears in every way to be a very successful and content young man. He's happily married, with a beautiful baby girl and an irrepressibly delightful three-year-old son. He's tall, good-looking, and healthy. He and his wife just bought their first house, and he's doing well at a great young company, working in genetic testing and health care. Reed is certainly enjoying all his recent success, but he doesn't think of it in those terms. He's mostly just grateful, and knows that how well it feels life is going is much more about his mind-set than his current level of success.

This is the real reason why Reed is winning at life.

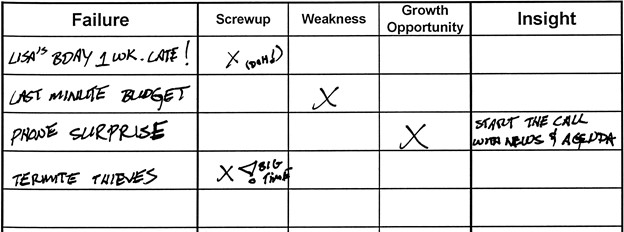

Failure Reframe Exercise

It's easy for us to describe the lofty goal of attaining failure immunity, but getting there is another matter. Here's an exercise to help you do just that—the failure reframe. Failure is the raw material of success, and the failure reframe is a process of converting that raw material into real growth. It's a simple three-step exercise:

1. Log your failures.

2. Categorize your failures.

3. Identify growth insights.

Log Your Failures

Just write down when you've messed up. You can do this by looking back over the last week, the last month, the last year, or make it your All-Time Failure Hits List. Any time frame can work. If you want to build the habit of converting failures to growth, then we suggest you do this once or twice a month until you've established a new way of thinking. Failure reframe is a healthy habit that leads to failure immunity.

Categorize Your Failures

It's useful to categorize failures into three types so you can more easily identify where the growth potential lies.

Screwups are just that—simple mistakes about things that you normally get right. It's not that you can't do better. You normally do these things right, so you don't really need to learn anything from this—you just screwed up. The best response here is to acknowledge you screwed up, apologize as needed, and move on.

Weaknesses are failures that happen because of one of your abiding failings. These are the mistakes that you make over and over. You know the source of these failures well. They are old friends. You've probably worked at correcting them already, and have improved as far as you think you're going to. You try to avoid getting caught by these weaknesses, but they happen. We're not suggesting you cave in prematurely and accept mediocre performance, but we are suggesting that there isn't much upside in trying to change your stripes. It's a judgment call, of course, but some failures are just part of your makeup, and your best strategy is avoidance of the situations that prompt them instead of improvement.

Growth opportunities are the failures that didn't have to happen, or at least don't have to happen the next time. The cause of these failures is identifiable, and a fix is available. We want to direct our attention here, rather than get distracted by the low return on spending too much time on the other failure types.

Do any of the growth opportunity failures offer an invitation for a real improvement? What is there to learn here? What went wrong (the critical failure factor)? What could be done differently next time (the critical success factor)? Look for an insight to capture that could change things next time. Jot it down and put it to work. That's it—a simple reframe.

Here are some examples from Dave's almost endlessly long failure log.

Dave did actually miss his daughter Lisa's birthday. By exactly a week. He doesn't remember this sort of thing well at all (a weakness), so he uses his calendar to remind himself. But one year he accidentally wrote it on the wrong week. He carefully planned a nice birthday dinner out with her—seven days after her birthday. He managed to stay in the dark for the whole week by being on the road. Total screwup. Weird mistake. Not going to happen again. Another awful screwup was getting robbed. While the house was being fumigated for termites, Dave and his wife had to move out for three days, during which time thieves broke into the tented house and stole everything of value. It was awful. What did he do wrong? He didn't hire a private guard to watch the house for three days. But who does that? The police said it was a very odd situation (most thieves aren't willing to be lethally fumigated to get your TV set), and all of Dave's friends had gone through getting fumigated without even hearing about hiring a guard. Though the failure had been preventable, it was so unusual that he accepted it as merely a screwup. Huge, painful, and expensive, but—just a screwup.

Then he had to stay up half the night (again) to get his budget in on time the next day. Dave is a famous procrastinator. He has lots of tricks to solve this persistent failing, and they work a good 7 percent of the time. He's learned to work around it most of the time and just live with it the rest of the time. He almost never misses a deadline—he just gets to stay up late a lot. Big deal. There's apparently not much left to learn here. Been there, still doing that. It's a weakness.

He was very surprised while talking on the phone to a client not long ago. Dave had just opened the conversation with a marketing question about the project they were working on when the client lost her temper and started yelling. Dave was floored. He'd not heard that the key engineer on the project had quit and everything was in shambles. Though it was the scheduled reason for his call, his lengthy opening question about marketing was now irrelevant, and the client was furious that he was wasting her time. That is not the sort of mistake Dave is used to making. He's actually pretty great at client management, and talks on the phone a few dozen hours a week. So what happened this time? As he thought about it, he realized that the mistake was launching right into the agenda of the call without checking in first. Almost all Dave's calls are scheduled with an agenda topic and a tight time frame. He usually has great success if he launches into the agenda right away, but now he realized that he never does that when he meets people in person.

In a live meeting, he starts with a check-in to see how the person is and what news has developed since their last contact, and he always confirms the agenda before getting down to business. He often discovers important news during that check-in, but he stopped doing it some time ago on the phone, in the interest of saving time. Skipping it was clearly a risk; he just hadn't gotten caught until now. The insight was clear—do a quick news-and-agenda check, even in phone calls. It only takes a few seconds and can make a huge difference.

Dave needed less time to analyze those five failures than it took you to read about them. This exercise is not hard, but it can bring big rewards. If Dave had just left that bad phone call saying, “Sheesh! What's her problem, anyway?,” he'd have learned nothing and would still be at risk of doing it again. Similarly, if he'd not thought about what led to that awful robbery or blowing his daughter's birthday, he would still be beating himself up about those situations needlessly—to no productive end.

A little failure reframing can go a long way to building up your failure immunity. Give it a try.

Don't Fight Reality

Even if you have your dream job and your dream life, stuff will still hit the fan. Designers know a lot about how things don't work out as planned. When you understand who you are, design your life, and then go live your life, you cannot fail. It does not mean that you won't stumble or that a particular prototype will always work as expected. But failure immunity comes from knowing that a prototype that did not work still leaves you with valuable information about the state of the world here—at your new starting point. When obstacles happen, when your progress gets derailed, when the prototype changes unexpectedly—life design lets you turn absolutely any change, setback, or surprise into something that can contribute to who you are becoming personally and professionally.

Life designers don't fight reality. They become tremendously empowered by designing their way forward no matter what. In life design, there are no wrong choices; there are no regrets. There are just prototypes, some that succeed and some that fail. Some of our greatest learning comes from a failed prototype, because then we know what to build differently next time. Life is not about winning and losing. It's about learning and playing the infinite game, and when we approach our lives as designers, we are constantly curious to discover what will happen next.

The only question that remains is one we've all heard a time or two before: What would you do if you knew you could not fail?

Try Stuff

Reframing Failure

1. Using the worksheet below (or downloading it from www.designingyour.life), look back over the last week (or month or year), and log your failures.

2. Categorize them as screwups, weaknesses, or growth opportunities.

3. Identify your growth insights.

4. Build a habit of converting failures to growth by doing this once or twice a month.