Part Two

Honesty is stronger medicine than sympathy,

which may console but often conceals.

—Gretel Ehrlich

Chapter 18 Fridays at Four

We're in my colleague Maxine's office—skirted chairs, distressed wood, vintage fabrics, and soft shades of cream. It's my turn to present a case in today's consultation group, and I want to talk about a patient I can't seem to help.

Is it her? Is it me? That's what I'm here to find out.

Becca is thirty years old, and she came to me a year ago because of difficulty with her social life. She did well at her work but felt hurt that her peers excluded her, never inviting her to join them for lunch or drinks. Meanwhile, she'd just dated a string of men who seemed excited at first but broke it off after two months.

Was it her? Was it them? That's what she'd come to therapy to find out.

This isn't the first time I've brought up Becca on a Friday at four, when our weekly group meets. Though not required, consultation groups are a fixture of many therapists' lives. Working alone, we don't have the benefit of input from others, whether that's praise for a job well done or feedback on how to do better. Here we examine not just our patients but ourselves in relation to our patients.

In our group, Andrea can say to me, "That patient sounds like your brother. That's why you're responding that way." I can help Ian manage his feelings about the patient who begins her sessions by reporting her horoscope ("I can't stand this woo-woo shit," he says). Group consultation is a system—imperfect, but valuable—of checks and balances to ensure that we're maintaining objectivity, homing in on the important themes, and not missing anything obvious in the treatment.

Admittedly, there's also banter on these Friday afternoons—often along with food and wine.

"It's the same dilemma," I tell the group—Maxine, Andrea, Claire, and Ian, our lone male. Everyone has blind spots, I add, but what's notable about Becca is that she seems to have so little curiosity about herself.

The members of the group nod. Many people begin therapy more curious about others than about themselves—Why does my husband do this? But in each conversation, we sprinkle seeds of curiosity, because therapy can't help people who aren't curious about themselves. At some point I might even say something like "I wonder why I seem to be more curious about you than you are about yourself?" and see where the patient takes this. Most people will start to get curious about my question. But not Becca.

I take a breath and go on. "She's not satisfied with what I'm doing, she's not moving forward, and instead of seeing somebody else, she comes each week—almost to show that she's right and I'm wrong."

Maxine, who's been in practice for thirty years and is the matriarch of the group, swirls the wine in her glass. "Why do you keep seeing her?"

I consider this as I slice some cheese from the wedge on the tray. In fact, all of the ideas the group has offered in the past several of months have fallen flat. If, for instance, I asked Becca what her tears were about, she'd shoot back with "That's why I'm coming to you—if I knew what was going on, I wouldn't need to be here." If I talked about what was happening between us in the moment—her disappointment in me, her feeling misunderstood by me, her perception that I wasn't helpful—she'd go off on a tangent about how this kind of impasse didn't happen with anybody else, just me. When I attempted to keep the conversation focused on us—did she feel accused of something, or criticized?—she'd get angry. When I tried to talk about the anger, she'd shut down. When I wondered if the shutting down was a way of keeping out what I had to say for fear it might hurt her, she'd say again that I misunderstood. If I asked why she kept coming to see me if she felt so misunderstood, she'd say I was abandoning her and that I wished she would leave—just like her boyfriends or her peers at work. When I tried to help her consider why those people pulled away from her, she'd say the boyfriends were commitment-phobes and her coworkers were snobby.

Generally what happens between therapist and patient also plays out between the patient and people in the outside world, and it's in the safe space of the therapy room that the patient can begin to understand why. (And if the dance between therapist and patient doesn't play out in the patient's outside relationships, it's often because the patient doesn't have any deep relationships—precisely for this reason. It's easy to have smooth relationships on a surface level.) It seemed that Becca was reenacting with me and everyone else a version of her relationship with her parents, but she wasn't willing to discuss that either.

Of course, there are times when something just isn't right between therapist and patient, when the therapist's countertransference is getting in the way. One sign: having negative feelings about the patient.

Becca does irritate me, I tell the group. But is it because she reminds me of somebody from my past, or because she's genuinely difficult to interact with?

Therapists use three sources of information when working with patients: What the patients say, what they do, and how we feel while we're sitting with them. Sometimes a patient will basically be wearing a sign around her neck saying I REMIND YOU OF YOUR MOTHER! But as a supervisor drilled into us during training, "What you feel on the receiving end of an encounter with a patient is real—use it." Our experiences with this person are important because we're probably feeling something pretty similar to what everyone else in this patient's life feels.

Knowing that helped me empathize with Becca, to see how deep her struggles were. The late reporter Alex Tizon believed that every person has an epic story that resides "somewhere in the tangle of the subject's burden and the subject's desire." But I couldn't get there with Becca. I felt increasingly fatigued in our sessions—not from mental exertion, but from boredom. I made sure to have chocolate and do jumping jacks before she came in to wake myself up. Eventually, I moved her evening session to first thing in the morning. The minute she sat down, though, the boredom set in and I felt helpless to help her.

"She needs to make you feel incompetent so she can feel more powerful," Claire, a sought-after analyst, says today. "If you fail, then she doesn't have to feel like such a failure."

Maybe Claire is right. The hardest patients aren't the ones like John, people who are changing but don't seem to realize it. The hardest patients are the ones, like Becca, who keep coming but don't change.

Recently Becca had started dating someone new, a guy named Wade, and last week, she told me about an argument they'd had. Wade had noticed that Becca seemed to complain about her friends quite a bit. "If you're so unhappy with them," he said, "why do you keep them as friends?"

Becca "couldn't believe" Wade's response. Didn't he understand that she was just venting? That she wanted to talk it through with him and not be "shut down"?

The parallels here seemed obvious. I asked Becca if she was just trying to vent with me and that, as with her friends, she found some value in our relationship, even though sometimes she also felt frustrated. No, Becca said, I'd gotten it wrong again. She was here to talk about Wade. She couldn't see that she had shut Wade down just as she had shut me down, which left her feeling shut down herself. She wasn't willing to look at what she was doing that made it difficult for people to give her what she wanted. Though Becca came to me wanting aspects of her life to change, she didn't seem open to actually changing. She was stuck in a "historical argument," one that predated therapy. And just as Becca had her limitations, so did I. Every therapist I know has come up against theirs.

Maxine asks again why I'm still seeing Becca. She points out that I've tried everything I know from my training and experience, everything I've gleaned from the therapists in my consultation group, and Becca is making no progress.

"I don't want her to feel emotionally stranded," I say.

"She already feels emotionally stranded," Maxine says. "By everyone in her life, including you."

"Right," I say. "But I'm afraid that if I end therapy with her, it's going to further cement her belief that nobody can help her."

Andrea raises her eyebrows.

"What?" I say.

"You don't need to prove your competence to Becca," she says.

"I know that. It's Becca I'm worried about."

Ian coughs loudly, then pretends to gag. The entire group bursts out laughing.

"Okay, maybe I do." I put some cheese on a cracker. "It's like this other patient I have who's in a relationship with a guy who doesn't treat her very well, and she won't leave because on some level, she wants to prove to him that she deserves to be treated better. She's never going to prove it to him, but she won't stop trying."

"You need to concede the fight," Andrea says.

"I've never broken up with a patient before," I say.

"Breakups are awful," Claire says, popping some grapes in her mouth. "But we'd be negligent if we didn't do them."

A collective Mm-hmm fills the room.

Ian watches, shaking his head. "You're all going to jump down my throat over this"—Ian's famous in our group for making generalizations about men and women—"but here's the thing. Women put up with more crap than men do. If a girlfriend's not treating a guy well, he has an easier time leaving. If a patient isn't benefiting from what I have to offer, and I've made sure I'm doing my very best but nothing's working, I'll break it off."

We give him our familiar stare-down: Women are just as good at letting go as men are. But we also know there might be a grain of truth here.

"To breaking it off," Maxine says, raising her glass. We clink glasses but not in a joyful way.

It's heartbreaking when a patient invests hope in you and, in the end, you know you've let her down. In those cases, a question stays with you: If I'd done something differently, if I'd found the key in time, could I have helped? The answer you give yourself: Probably. No matter what my consultation group says, I wasn't able to reach Becca in just the right way, and in that sense, I failed her.

Therapy is hard work—and not just for the therapist. That's because the responsibility for change lies squarely with the patient.

If you expect an hour of sympathetic head-nodding, you've come to the wrong place. Therapists will be supportive, but our support is for your growth, not for your low opinion of your partner. (Our role is to understand your perspective but not necessarily to endorse it.) In therapy, you'll be asked to be both accountable and vulnerable. Rather than steering people straight to the heart of the problem, we nudge them to arrive there on their own, because the most powerful truths—the ones people take the most seriously—are those they come to, little by little, on their own. Implicit in the therapeutic contract is the patient's willingness to tolerate discomfort, because some discomfort is unavoidable for the process to be effective.

Or as Maxine said one Friday afternoon: "I don't do ‘you go, girl' therapy."

It may seem counterintuitive, but therapy works best when people start getting better—when they feel less depressed or anxious, or the crisis has passed. Now they're less reactive, more present, more able to engage in the work. Unfortunately, sometimes people leave just as their symptoms lift, not realizing (or perhaps knowing all too well) that the work is just beginning and that staying will require them to work even harder.

Once, at the end of a session with Wendell, I told him that sometimes, on days when I left more upset than when I came in—tossed out into the world, having so much more to say, holding so many painful feelings—I hated therapy.

"Most things worth doing are difficult," he replied. He said this not in a glib way but in a tone and with an expression that made me think he spoke from personal experience. He added that while everyone wants to leave each session feeling better, I, of all people, should know that that's not always how therapy works. If I wanted to feel good in the short term, he said, I could eat a piece of cake or have an orgasm. But he wasn't in the short-term-gratification business.

And neither, he added, was I.

Except that I was—as a patient, that is. What makes therapy challenging is that it requires people to see themselves in ways they normally choose not to. A therapist will hold up the mirror in the most compassionate way possible, but it's up to the patient to take a good look at that reflection, to stare back at it and say, "Oh, isn't that interesting! Now what?" instead of turning away.

I decide to take my consultation group's advice and end my sessions with Becca. Afterwards, I feel both disappointed and liberated. When I tell Wendell about it at my next session, he says he knows exactly how it felt to be with her.

"You have patients like her?" I ask.

"I do," he says, and he smiles broadly, holding my gaze.

It takes a minute, but then I get it: He means me. Yikes! Does he do jumping jacks or down caffeine before our sessions too? Many patients wonder if they bore us with what feels to them like their unremarkable lives, but they're not boring at all. The patients who are boring are the ones who won't share their lives, who smile through their sessions or launch into seemingly pointless and repetitive stories every time, leaving us scratching our heads: Why are they telling me this? What significance does this have for them? People who are aggressively boring want to keep you at bay.

It's what I've done with Wendell when talking incessantly about Boyfriend; he can't quite reach me because I'm not allowing him to. And now he's laying it out there: I'm doing with him what Boyfriend and I did with each other—and I'm not so different from Becca after all.

"I'm telling you this by way of invitation," Wendell says, and I think about how many invitations of mine Becca had rebuffed. I don't want to do that with Wendell.

If I wasn't able to help Becca, maybe she'll be able to help me.

Chapter 19 What We Dream Of

One day, a twenty-four-year-old woman I'd been seeing for a few months came in and told me about the previous night's dream.

"I'm at the mall," Holly began, "and I run into this girl, Liza, who was horrible to me in high school. She didn't tease me to my face, like some other girls did. She just completely ignored me! Which would have been okay, except that if I ran into her outside of school, she'd pretend she had no idea who I was. Which was crazy, because we'd been at the same school for three years, and we had several classes together.

"Anyway, she lived a block away, so I'd run into her a lot—you know, around the neighborhood—and I'd have to pretend I didn't see her, because if I said hi or waved or acknowledged her in any way, she'd scrunch up her forehead and give me this look like she was trying to place me but couldn't. And then she'd say, in this fake-sweet voice, ‘I'm sorry, do I know you?' or ‘Have we met before?' or, if I was lucky, ‘This is so embarrassing, but what's your name again?'"

Holly's voice faltered for a second, then she continued.

"So in the dream, I'm at the mall, and Liza is there. I'm no longer in high school and I look different—I'm thin, wearing the perfect outfit, blow-dried hair. I'm flipping through some clothes on a rack when Liza comes over to browse through the same rack, and she starts making small talk about the clothes, the way you might with a stranger. At first I'm pissed, like here we go again—she's still pretending not to recognize me. Except then I realize that now it's real—she doesn't recognize me because I look so good."

Holly shifted on the couch, covering herself with the blanket. We've talked in the past about how she uses that blanket to cover up her body, to hide her size.

"So I play innocent, and we start chatting about the clothes and what our jobs are, and as I'm talking, I see this look of recognition dawning on her face. It's like she's trying to reconcile her image of me from twelfth grade—you know, pimply, fat, frizzy hair—with me now. I see her brain connecting the dots, and then she says, ‘Oh my God! Holly! We went to high school together!'"

Holly was starting to laugh now. She was tall and striking, with long chestnut hair and eyes the color of a tropical ocean, and she was still a good forty pounds overweight.

"So," she continued, "I scrunch up my forehead and say, in the same fake-sweet voice she used to use on me, ‘Wait, I'm so sorry. Do I know you?' And she says, ‘Of course you know me—it's Liza! We had geometry and ancient history and French together—remember Ms. Hyatt's class?' And I say, ‘Yeah, I had Ms. Hyatt, but, gosh, I don't remember you. You were in that class?' And she says, ‘Holly! We lived a block away from each other. I used to see you at the movies and the yogurt place and that one time in Victoria's Secret by the dressing rooms—'"

Holly laughed some more.

"She's totally giving away that she did know me all those times. But I say, ‘Wow, how weird, I don't remember you, but it's nice to meet you.' And then my phone rings and it's her high-school boyfriend telling me to hurry up, we'll be late for our movie. So I give her that condescending smile she used to give me, and I walk away, leaving her feeling how I felt in high school. And then I realize that the ringing phone is actually my alarm and it was all a dream."

Later, Holly would call this her "poetic-justice dream," but to me it was about a common theme that comes up in therapy, and not just in dreams—the theme of exclusion. It's the fear that we'll be left out, ignored, shunned, and end up unlovable and alone.

Carl Jung coined the term collective unconscious to refer to the part of the mind that holds ancestral memory, or experience that is common to all humankind. Whereas Freud interpreted dreams on the object level, meaning how the content of the dream related to the dreamer in real life (the cast of characters, the specific situations), in Jungian psychology, dreams are interpreted on the subject level, meaning how they relate to common themes in our collective unconscious.

It's no surprise that we often dream about our fears. We have a lot of fears.

What are we afraid of?

We are afraid of being hurt. We are afraid of being humiliated. We are afraid of failure and we are afraid of success. We are afraid of being alone and we are afraid of connection. We are afraid to listen to what our hearts are telling us. We are afraid of being unhappy and we are afraid of being too happy (in these dreams, inevitably, we're punished for our joy). We are afraid of not having our parents' approval and we are afraid of accepting ourselves for who we really are. We are afraid of bad health and good fortune. We are afraid of our envy and of having too much. We are afraid to have hope for things that we might not get. We are afraid of change and we are afraid of not changing. We are afraid of something happening to our kids, our jobs. We are afraid of not having control and afraid of our own power. We are afraid of how briefly we are alive and how long we will be dead. (We are afraid that after we die, we won't have mattered.) We are afraid of being responsible for our own lives.

Sometimes it takes a while to admit our fears, especially to ourselves.

I've noticed that dreams can be a precursor to self-confession—a kind of pre-confession. Something buried is brought closer to the surface, but not in its entirety. A patient dreams that she's lying in bed hugging her roommate; initially she thinks it's about their strong friendship but later she realizes she's attracted to women. A man has a recurring dream that he's been caught speeding on the freeway; a year into this dream, he begins to consider that his decades of cheating on his taxes—of positioning himself above the rules—might catch up with him.

After I've been seeing Wendell for a few months, my patient's dream about her high-school classmate seeps into mine. I'm at the mall, looking through a rack of dresses, when Boyfriend appears at the same rack. Apparently, he's shopping for a birthday gift for his new girlfriend.

"Oh, which birthday?" I ask in the dream.

"Fiftieth," he says. At first I'm relieved in the pettiest way—not only is she not the clichéd twenty-five-year-old, but she's actually older than I am. It makes sense. Boyfriend wanted no kids in the house, and she's old enough to have kids in college. Boyfriend and I are having a pleasant conversation—friendly, innocuous—until I happen to catch a glimpse of myself in the mirror adjacent to the rack. That's when I see that I'm actually an old lady—late seventies, maybe eighties. It turns out that Boyfriend's fifty-year-old girlfriend is, in fact, decades younger than I am.

"Did you ever write your book?" Boyfriend asks.

"What book?" I say, watching my wrinkled, prune-like lips move in the mirror.

"The book about your death," he replies matter-of-factly.

And then my alarm goes off. All day, as I hear other patients' dreams, I can't stop thinking about mine. It haunts me, this dream.

It haunts me because it's my pre-confession.

Chapter 20 The First Confession

Allow me to get defensive for a minute. You see, when I told Wendell that everything was just fine until the breakup, I was telling the absolute truth. Or, rather, the truth as I knew it. Which is to say, the truth as I wanted to see it.

And now let me remove the defense: I was lying.

One thing I haven't told Wendell is that I'm supposed to be writing a book—and that it hasn't been going very well. By "not going very well," I mean that I haven't actually been writing it. This wouldn't be a problem if I weren't under contract and therefore legally obligated to either produce a book or return the advance that I no longer have in my bank account. Well, it would still be a problem even if I could return the money, because in addition to being a therapist, I am a writer—it's not just what I do but who I am—and if I can't write, then a crucial part of me goes missing. And if I don't turn in this book, my agent says that I won't get the opportunity to write another.

It isn't that I haven't been able to write at all. In fact, during the time I was supposed to be writing my book, I was crafting fabulously witty and flirtatious emails to Boyfriend, all while telling friends and family and even Boyfriend that I was busy writing my book. I was like the closet gambler who gets dressed for work and kisses his family goodbye each morning and then drives to the casino instead of the office.

I've been meaning to talk to Wendell about this situation, but I've been so focused on getting through the breakup that I haven't had a chance.

Obviously that, too, is a big fat lie.

I haven't told Wendell about the book-I'm-not-writing because every time I think about it, I'm filled with panic, dread, regret, and shame. Whenever the situation pops into my head (which is constantly; as Fitzgerald put it, "In a real dark night of the soul, it is always three o'clock in the morning, day after day"), my stomach tightens and I feel paralyzed. Then I question every bad decision I've made at various forks in the road because I'm convinced that I'm in this current situation due to what ranks as one of the most colossally bad decisions of my life.

Perhaps you're thinking, Really? You were lucky enough to get a book contract, and now you're not writing the book? Boo-hoo! Try working twelve hours a day in a factory, for God's sake! I understand how this comes across. I mean, who do I think I am, Elizabeth Gilbert at the beginning of Eat, Pray, Love when she's crying on the bathroom floor as she thinks about leaving the husband who loves her? Gretchen Rubin in The Happiness Project who has the loving, handsome husband, the healthy daughters, and more money than most people will ever see but still has that niggling feeling of something missing?

Which reminds me—I left out an important detail about the book-I'm-not-writing. The topic? Happiness. No, the irony hasn't been lost on me: the happiness book has been making me miserable.

I should never have been writing a happiness book in the first place, and not just because, if Wendell's grieving-something-bigger theory holds water, I've been depressed. When I made the decision to write this book, I'd recently begun my private practice, and I'd just written a cover story for the Atlantic called "How to Land Your Kid in Therapy: Why Our Obsession with Our Kids' Happiness May Be Dooming Them to Unhappy Adulthoods," which, at the time, was the most emailed piece in the hundred-plus-year history of the magazine. I talked about it on national television and radio; media from around the world called me for interviews; and overnight, I became a "parenting expert."

Next thing I knew, publishers wanted the book version of "How to Land Your Kid in Therapy." By wanted, I mean they wanted it for—I don't know how else to say this—a dizzying sum of money. It was the kind of money that a single mom like me only dreamed of, the kind of money that would provide our one-income family with some financial room to breathe for a long time. A book like this would have led to speaking engagements (which I enjoy) at schools across the country and a steady flow of patients (which would have helped, as I was starting out). The article was even optioned for a television series (which might have gotten made had there also been a best-selling book to go along with it).

But when given the opportunity to write the book version of "How to Land Your Kid in Therapy," a book that could potentially change the entire landscape of my professional and financial future, I said, with an astonishing lack of forethought: Thanks very much, that's so kind, but . . . I'd rather not.

I hadn't had a stroke. I just said no.

I said no because something felt wrong about it. Mainly, I didn't think that the world needed another helicopter-parenting book. Dozens of smart, thoughtful books had already covered overparenting from every conceivable angle. After all, two hundred years ago, the philosopher Johann Wolfgang von Goethe succinctly summarized this sentiment: "Too many parents make life hard for their children by trying, too zealously, to make it easy for them." Even in recent history—2003, to be exact—one of the early modern overparenting books, aptly named Worried All the Time, put it this way: "The cardinal rules of good parenting—moderation, empathy, and temperamental accommodation with one's child—are simple and are not likely to be improved upon by the latest scientific findings."

As a mom myself, I wasn't immune to parental anxiety. I wrote my original article, in fact, with the hope that it would be useful to parents in the way that a therapy session might be. But if I eked a book out of it in order to jump on the commercial bandwagon and join the ranks of insta-experts, I thought I'd be part of the problem. What parents needed, I believed, wasn't another book about how they had to calm down and take a break. What they needed was an actual break from the deluge of parenting books. (The New Yorker later ran a humor piece about the proliferation of parenting manifestos, saying that "another book at this point would just be cruel.")

So like Bartleby the Scrivener (and with similarly tragic results), I said, "I would prefer not to." Then I spent the next several years watching more and more overparenting books hit the market and beating myself up with a rotating roster of self-flagellating questions: Had I been a responsible adult by turning down that kind of money? I'd recently finished an unpaid internship, I had graduate-school loans to repay, and I was the sole provider for my family; why couldn't I have just written the parenting book quickly, reaped the professional and financial benefits, and gone my merry way? After all, how many people have the luxury of working only on what matters most to them?

The regret I felt about having not done the parenting book was compounded by the fact that I continued to get weekly reader mail and speaking-engagement queries about the "How to Land Your Kid in Therapy" article. "Will there be a book?" person after person asked. No, I wanted to reply, because I'm a moron.

I did feel like a moron, because in the interest of not selling out and cashing in on the parenting craze, I agreed instead to write the now-dreaded, depression-inducing happiness book. To make ends meet as I launched my practice, I still had to write a book, and I thought at the time that I could provide a service to readers. Instead of showing how we parents were trying too hard to make our kids happy, I was going to show how we were trying too hard to make ourselves happy. This idea seemed closer to my heart.

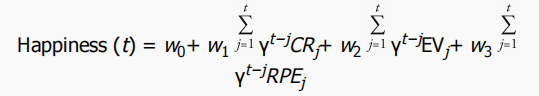

But whenever I sat down to write, I felt as disconnected from the topic as I had from the subject of helicopter parenting. The research didn't—couldn't—reflect the subtleties of what I was seeing in the therapy room. Some scientists had even come up with a complex mathematical equation to predict happiness based on the premise that happiness stems not from how well things go but whether things go better than expected. It looks like this:

Which all boils down to: Happiness equals reality minus expectations. Apparently, you can make people happy by delivering bad news and then taking it back (which, personally, would just make me mad).

Still, I knew I could put together some interesting studies, but I felt I'd just be scratching the surface of something else I wanted to say but couldn't quite put my finger on. And in my new career, and in my life more generally, scratching the surface no longer felt satisfying. You can't go through psychotherapy training and not be changed in some way, not become, without even noticing, oriented toward the core.

I told myself it didn't matter. Just write the book and be done with it. I'd already botched things up with the parenting book; I couldn't botch up this happiness book too. And yet, day after day, I couldn't get myself to write it. Just like I couldn't get myself to write the parenting book. How had I gotten here again?

In graduate school, we used to watch therapy sessions through one-way mirrors, and sometimes when I'd sit down to write the happiness book, I'd think about a thirty-five-year-old patient I'd observed. He'd come to therapy because he very much loved and was attracted to his wife but he couldn't stop cheating on her. Neither he nor his wife understood how his behavior could be so at odds with what he believed he wanted—trust, stability, closeness. In his session, he explained that he hated the turmoil his cheating put his wife and their marriage through and knew that he wasn't the husband or father he wanted to be. He talked for a while about how desperately he wanted to stop cheating and how he had no idea why he kept doing it.

The therapist explained that often different parts of ourselves want different things, and if we silence the parts we find unacceptable, they'll find other ways to be heard. He asked the guy to sit in a different chair, across the room, and see what happened when the part of him that chose to cheat wasn't shoved aside but got to say its piece.

At first the poor guy was at a loss, but gradually, he began to give voice to his hidden self, the part that would goad the responsible, loving husband into engaging in self-defeating behavior. He was torn between these two aspects of himself, just as I was torn between the part of me that wanted to provide for my family and the part of me that wanted to do something meaningful—something that touched my soul and hopefully others' souls as well.

Boyfriend appeared on the scene just in time to distract me from this internal battle. And once he was gone, I filled the void by Google-stalking him when I should have been writing. So many of our destructive behaviors take root in an emotional void, an emptiness that calls out for something to fill it. But now that Wendell and I have talked about not Google-stalking Boyfriend, I feel accountable. I have no excuse not to sit down and write this misery-inducing happiness book.

Or at least tell Wendell the truth about the mess I'm in.

Chapter 21 Therapy with a Condom On

"Hi, it's me," I hear as I listen to my voicemails between sessions. My stomach lurches; it's Boyfriend. Though it's been three months since we've spoken, his voice instantly transports me back in time, like hearing a song from the past. But as the message continues, I realize it's not Boyfriend because (a) Boyfriend wouldn't call my office number and (b) Boyfriend doesn't work on a TV show.

This "me" is John (eerily, Boyfriend and John have similar voices, deep and low) and it's the first time a patient has called my office without leaving a name. He does this as if he's the only patient I have, not to mention the only "me" in my life. Even suicidal patients will leave their names. I've never gotten Hi, it's me. You told me to call if I was feeling like killing myself.

John says in his message that he can't make our session today because he's stuck at the studio, so he'll be Skyping in instead. He gives me his Skype handle, then says, "Talk to you at three."

I note that he doesn't ask if we can Skype or inquire whether I do Skype sessions in the first place. He just assumes it will happen because that's how the world works for him. And while I'll Skype with patients under certain circumstances, I think it's a bad idea with John. So much of what I'm doing to help him relies on our in-the-room interaction. Say what you will about the wonders of technology, but screen-to-screen is, as a colleague once said, "like doing therapy with a condom on."

It's not just the words people say or even the visual cues that therapists notice in person—the foot that shakes, the subtle facial twitch, the quivering lower lip, the eyes narrowing in anger. Beyond hearing and seeing, there's something less tangible but equally important—the energy in the room, the being together. You lose that ineffable dimension when you aren't sharing the same physical space.

(There's also the issue of glitches. I was once on a Skype session with a patient who was in Asia temporarily, and just as she began crying hysterically, the volume went out. All I saw was her mouth moving, but she didn't know that I couldn't hear what she was saying. Before I could get that across, the connection dropped entirely. It took ten minutes to restore the Skype, and by then not only was the moment lost but our time had run out.)

I send John a quick email offering to reschedule, but he types back a message that reads like a modern-day telegram: Can't w8. Urgent. Please. I'm surprised by the please and even more by his acknowledgment of needing urgent help—of needing me, rather than treating me as dispensable. So I say okay, we'll Skype at three.

Something, I figure, must be up.

At three, I open Skype and click Call, expecting to find John sitting in an office at a desk. Instead, the call connects and I'm looking into a familiar house. It's familiar to me because it's one of the main sets of a TV show that Boyfriend and I used to binge-watch on my sofa, arms and legs entwined. Here, camera and lighting people are moving about, and I'm staring at the interior of a bedroom I've seen a million times. John's face comes into view.

"Hang on a second" is how he greets me, and then his face disappears and I'm looking at his feet. Today he's wearing trendy checkered sneakers, and he seems to be walking somewhere while carrying me with him. Presumably he's looking for privacy. Along with his shoes, I see thick electrical wires on the floor and hear a commotion in the background. Then John's face reappears.

"Okay," he says. "I'm ready."

There's a wall behind him now, and he starts rapid-fire whispering.

"It's Margo and her idiot therapist. I don't know how this person has a license but he's making things worse, not better. She was supposed to be getting help for her depression but instead she's getting more upset with me: I'm not available, I'm not listening, I'm distant, I avoid her, I forgot something on the calendar. Did I tell you that she created a shared Google calendar to make sure I won't forget things that are ‘important'"—with his free hand, John does an air quote as he says the word important—"so now I'm even more stressed because my calendar is filled with Margo's things and I've already got a packed schedule!"

John has gone over this with me before so I'm not sure what the urgency is about today. Initially he had lobbied Margo to see a therapist ("So she can complain to him") but once she started going, John often told me that this "idiot therapist" was "brainwashing" his wife and "putting crazy ideas in her head." My sense has been that the therapist is helping Margo gain more clarity about what she will and will not put up with and that this exploration has been long overdue. I mean, it can't be easy being married to John.

At the same time, I empathize with John because his reaction is common. Whenever one person in a family system starts to make changes, even if the changes are healthy and positive, it's not unusual for other members in this system to do everything they can to maintain the status quo and bring things back to homeostasis. If an addict stops drinking, for instance, family members often unconsciously sabotage that person's recovery, because in order to regain homeostasis in the system, somebody has to fill the role of the troubled person. And who wants that role? Sometimes people even resist positive changes in their friends: Why are you going to the gym so much? Why can't you stay out late—you don't need more sleep! Why are you working so hard for that promotion? You're no fun anymore!

If John's wife becomes less depressed, how can John keep his role as the sane one in the couple? If she tries to get close in healthier ways, how can he preserve the comfortable distance he has so masterfully managed all of these years? I'm not surprised that John is having a negative reaction to Margo's therapy. Her therapist seems to be doing a good job.

"So," John continues, "last night, Margo asks me to come to bed, and I tell her I'll be there in a minute, I have to answer a few emails. Normally after about two minutes she'll be all over me—Why aren't you coming to bed? Why are you always working? But last night, she doesn't do any of that. And I'm amazed! I think, Jesus Christ, something's finally working in her therapy, because she's realizing that nagging me about coming to bed isn't going to get me in bed any faster. So I finish my emails, but when I get in bed, Margo's asleep. Anyway, this morning, when we wake up, Margo says, ‘I'm glad you got your work done, but I miss you. I miss you a lot. I just want you to know that I miss you.'"

John turns to his left and now I hear what he hears—a nearby conversation about lighting—and without his saying a word, I'm staring at John's sneakers again as they move across the floor. When I see his face appear this time, the wall behind him is gone, and now the star of the TV series is in the distant background in the upper-right corner of my screen, laughing with his on-camera nemesis along with the love interest he verbally abuses on the show. (I'm sure John is the one who writes this character.)

I love these actors, so now I'm squinting at the three of them through my screen like I'm one of those people behind the ropes at the Emmys trying to get a glimpse of a celebrity—except this isn't the red carpet and I'm watching them take sips from water bottles while they chat between scenes. The paparazzi would kill for this view, I think, and it takes massive willpower to focus solely on John.

"Anyway," he whispers, "I knew it was too good to be true. I thought she was being understanding last night, but of course the complaining starts up again first thing this morning. So I say, ‘You miss me? What kind of guilt trip is that?' I mean, I'm right here. I'm here every night. I'm one hundred percent loyal. Never cheated, never will. I provide a nice living. I'm an involved father. I even take care of the dog because Margo says she hates walking around with plastic bags of poop. And when I'm not there, I'm working. It's not like I'm off in Cabo all day. So I tell her I can quit my job and she can miss me less because I'll be twiddling my thumbs at home, or I can keep my job and we'll have a roof over our heads." He yells "I'll just be a minute!" to someone I can't see and then continues. "And you know what she does when I say this? She says, all Oprah-like"—here he does a dead-on impression of Oprah—"‘I know you do a lot, and I appreciate that, but I also miss you even when you're here.'"

I try to speak but John plows on. I haven't seen him this stirred up before.

"So for a second I'm relieved, because normally she'd yell at this point, but then I realize what's going on. This sounds nothing like Margo. She's up to something! And sure enough, she says, ‘I really need you to hear this.' And I say, ‘I hear it, okay? I'm not deaf. I'll try to come to bed earlier but I have to get my work done first.' But then she gets this sad look on her face, like she's about to cry, and it kills me when she gets that look, because I don't want to make her sad. The last thing I want to do is disappoint her. But before I can say anything, she says, ‘I need you to hear how much I miss you because if you don't hear it, I don't know how much longer I can keep telling you.' So I say, ‘We're threatening each other now?' and she says, ‘It's not a threat, it's the truth.'" John's eyes become saucers and his free hand juts into the air, palm up, as if to say, Can you believe this shit?

"I don't think she'd actually do it," he goes on, "but it shocked me because neither of us has ever threatened to leave before. When we got married we always said that no matter how angry we got, we would never threaten to leave, and in twelve years, we haven't." He looks to his right. "Okay, Tommy, let me take a look—"

John stops talking and suddenly I'm staring at his sneakers again. When he finishes with Tommy, he starts walking somewhere. A minute later his face pops up; he's in front of another wall.

"John," I say. "Let's take a step back. First, I know you're upset by what Margo said—"

"What Margo said? It's not even her! It's her idiot therapist acting as her ventriloquist! She loves this guy. She quotes him all the time, like he's her fucking guru. He probably serves Kool-Aid in the waiting room, and women all over the city are divorcing their husbands because they're drinking this guy's bullshit! I looked him up just to see what his credentials are and, sure enough, some moron therapy board gave him a license. Wendell Bronson, P-h-fucking-D."

Wait.

Wendell Bronson?

!

!!

!!!!

!!!!!!!

Margo is seeing my Wendell? The "idiot therapist" is Wendell? My mind explodes. I wonder where on the couch Margo chose to sit on her first day. I wonder if Wendell tosses her tissue boxes or if she sits close enough to reach them herself. I wonder if we've ever passed each other on the way in or out (the pretty crying woman from the waiting room?). I wonder if she's ever mentioned my name in her own therapy—"John has this awful therapist, Lori Gottlieb, who said . . ." But then I remember that John is keeping his therapy a secret from Margo—I'm the "hooker" he pays in cash—and right now, I'm tremendously grateful for this circumstance. I don't know what to do with this information, so I do what therapists are taught to do when we're having a complicated reaction to something and need more time to understand it. I do nothing—for the moment. I'll get consultation on this later.

"Let's stay with Margo for a second," I say, as much to myself as to John. "I think what she said was sweet. She must really love you."

"Huh? She's threatening to leave!"

"Well, let's look at it another way," I say. "We've talked before about how there's a difference between a criticism and a complaint, how the former contains judgment while the latter contains a request. But a complaint can also be an unvoiced compliment. I know that what Margo says often feels like a series of complaints. And they are—but they're sweet complaints because inside each complaint, she's giving you a compliment. The presentation isn't optimal, but she's saying that she loves you. She wants more of you. She misses you. She's asking you to come closer. And now she's saying that the experience of wanting to be with you and not having that reciprocated is so painful that she might not be able to tolerate it because she loves you so much." I wait to let him absorb that last part. "That's quite a compliment."

I'm always working with John on identifying his in-the-moment feelings, because feelings lead to behaviors. Once we know what we're feeling, we can make choices about where we want to go with them. But if we push them away the second they appear, often we end up veering off in the wrong direction, getting lost yet again in the land of chaos.

Men tend to be at a disadvantage here because they aren't typically raised to have a working knowledge of their internal worlds; it's less socially acceptable for men to talk about their feelings. While women feel cultural pressure to keep up their physical appearance, men feel that pressure to keep up their emotional appearance. Women tend to confide in friends or family members, but when men tell me how they feel in therapy, I'm almost always the first person they've said it to. Like my female patients, men struggle with marriage, self-esteem, identity, success, their parents, their childhoods, being loved and understood—and yet these topics can be tricky to bring up in any meaningful way with their male friends. It's no wonder that the rates of substance abuse and suicide in middle-aged men continue to increase. Many men don't feel they have any other place to turn.

So I let John take his time to sort out his feelings about Margo's "threat" and the softer message that might be behind it. I haven't seen him sit with his feelings this long before, and I'm impressed that he's able to do so now.

John's eyes have darted down and to the side, which is what usually happens with someone when what I'm saying touches someplace vulnerable, and I'm glad. It's impossible to grow without first becoming vulnerable. It looks like he's still really taking this in, that for the first time, his impact on Margo is resonating.

Finally John looks back up at me. "Hi, sorry, I had to mute you back there. They were taping. I missed that. What were you saying?"

Un-fucking-believable. I've been, quite literally, talking to myself. No wonder Margo wants to leave! I should have listened to my gut and had John reschedule an in-person session, but I got sucked in by his urgent plea.

"John," I say, "I really want to help you with this but I think this is too important to talk about on Skype. Let's schedule a time for you to come in so there aren't so many distract—"

"Oh, no, no, no, no, no," he interrupts. "This can't wait. I just had to give you the background first so you can talk to him."

"To . . ."

"The idiot therapist! Clearly he's only hearing one side of the story, and not a very accurate side at that. But you know me. You can vouch for me. You can give this guy some perspective before Margo really goes nuts."

I noodle this scenario around in my head: John wants me to call my own therapist to discuss why my patient isn't happy with the therapy my therapist is doing with my patient's wife.

Um, no.

Even if Wendell weren't my therapist, I wouldn't make this call. Sometimes I'll call another therapist to discuss a patient if, say, I'm seeing a couple and a colleague is seeing one member of the couple, and there's a compelling reason to exchange information (somebody is suicidal or potentially violent, or we're working on something in one setting that it would be helpful to have reinforced in another, or we want to get a broader perspective). But on these rare occasions, the parties will have signed releases to this effect. Wendell or no Wendell, I can't call up the therapist of my patient's wife for no clinically relevant reason and without both patients signing consent forms.

"Let me ask you something," I say to John.

"What?"

"Do you miss Margo?"

"Do I miss her?"

"Yes."

"You're not going to call Margo's therapist, are you?"

"I'm not, and you're not going to tell me how you really feel about Margo, are you?" I have a feeling that there's a lot of buried love between John and Margo because I know this: love can often look like so many things that don't seem like love.

John smiles as I see somebody who I assume is Tommy again enter the frame holding a script. I'm flipped toward the ground with such speed that I get dizzy, as if I'm on a roller coaster that just took a quick dive. Staring at John's shoes, I hear some back-and-forth about whether the character—my favorite!—is supposed to be a complete asshole in this scene or maybe have some awareness that he's being an asshole (interestingly, John picks awareness) and then Tommy thanks John and leaves. To my amusement, John seems perfectly pleasant, apologizing to Tommy for his absence and explaining to him that he's busy "putting out a fire with the network." (I'm "the network.") Maybe he's polite to his coworkers after all.

Or maybe not. He waits for Tommy to leave, then lifts me up to face level again and mouths, Idiot, rolling his eyes in Tommy's direction.

"I just don't understand how her therapist, who's a guy, can't see both sides of this," he continues. "Even you can see both sides of this!"

Even me? I smile. "Was that a compliment you just gave me?"

"No offense. I just meant . . . you know."

I do know, but I want him to say it. In his own way, he's becoming attached to me, and I want him to stay in his emotional world a bit longer. But John goes back to his tirade about Margo pulling the wool over her therapist's eyes and how Wendell is a quack because his sessions are only forty-five minutes, not the typical fifty. (This bugs me too, by the way.) It occurs to me that John is talking about Wendell the way a husband might talk about a man his wife has a crush on. I think he's jealous and feels left out of whatever goes on between Margo and Wendell in that room. (I'm jealous too! Does Wendell laugh at Margo's jokes? Does he like her better?) I want to bring John back to that moment when he almost connected with me.

"I'm glad that you feel understood by me," I say. John gets a deer-in-the-headlights look on his face for a second, then moves on.

"All I want to know is how to deal with Margo."

"She already told you," I say. "She misses you. I can see from our experience together how skilled you are at pushing away people who care about you. I'm not leaving, but Margo's saying she might. So maybe you'll try something different with her. Maybe you'll let her know that you miss her too." I pause. "Because I might be wrong, but I think you do miss her."

He shrugs, and this time when he looks down, I'm not on mute. "I miss the way we were," he says.

His expression is sad instead of angry now. Anger is the go-to feeling for most people because it's outward-directed—angrily blaming others can feel deliciously sanctimonious. But often it's only the tip of the iceberg, and if you look beneath the surface, you'll glimpse submerged feelings you either weren't aware of or didn't want to show: fear, helplessness, envy, loneliness, insecurity. And if you can tolerate these deeper feelings long enough to understand them and listen to what they're telling you, you'll not only manage your anger in more productive ways, you also won't be so angry all the time.

Of course, anger serves another function—it pushes people away and keeps them from getting close enough to see you. I wonder if John needs people to be angry at him so that they won't see his sadness.

I start to speak, but somebody yells John's name, startling him. The phone slips out of his hand and careens toward the floor, but just as I feel like my face might hit the ground, John catches it, bringing himself back into view. "Crap—gotta go!" he says. Then, under his breath: "Fucking morons." And the screen goes blank.

Apparently, our session is over.

With time to spare before my next session, I head into the kitchen for a snack. Two of my colleagues are there. Hillary is making tea. Mike's eating a sandwich.

"Hypothetically," I say, "what would you do if your patient's wife was seeing your therapist, and your patient thought your therapist was an idiot?"

They look up at me, eyebrows raised. Hypotheticals in this kitchen are never hypothetical.

"I'd switch therapists," Hillary says.

"I'd keep my therapist and switch patients," Mike says.

They both laugh.

"No, really," I say. "What would you do? It gets worse: He wants me to talk to my therapist about his wife. His wife doesn't know he's in therapy yet, so it's a non-issue now, but what if at some point he tells her and then wants me to consult with my therapist about his wife, and his wife consents? Do I have to disclose that he's my therapist?"

"Absolutely," Hillary says.

"Not necessarily," Mike says at the same time.

"Exactly," I say. "It's not clear. And you know why it's not clear? Because this kind of thing NEVER HAPPENS! When has something like this ever happened?"

Hillary pours me some tea.

"I once had two people come to me individually for therapy right after they'd separated," Mike says. "They had different last names and listed different addresses because of the separation, so I didn't know they were married until the second session with each of them, when I realized I was hearing the same stories from different sides. Their mutual friend, who was a former patient, gave both of them my name. I had to refer them out."

"Yeah," I say, "but this isn't two patients with a conflict of interest. My therapist is mixed up in this. What are the odds of that?"

I notice Hillary looking away. "What?" I say.

"Nothing."

Mike looks at her. She blushes. "Spill it," he says.

Hillary sighs. "Okay. About twenty years ago, when I was first starting out, I was seeing a young guy for depression. I felt like we were making progress, but then the therapy seemed to stall. I thought he wasn't ready to move forward, but really I just didn't have enough experience and was too green to know the difference. Anyway, he left, and about a year later, I ran into him at my therapist's."

Mike grins. "Your patient left you for your own therapist?"

Hillary nods. "The funny thing is, in therapy, I talked about how stuck I was with this patient and how helpless I felt when he left. I'm sure the patient later told my therapist about his inept former therapist and used my name at some point. My therapist had to have put two and two together."

I think about this in relation to the Wendell situation. "But your therapist never said anything?"

"Never," Hillary says. "So one day I brought it up. But of course she can't say that she sees this guy, so we kept the conversation focused on how I deal with the insecurities of being a new therapist. Pfft. My feelings? Whatever. I was just dying to know how their therapy was going and what she did differently with him that worked better."

"You'll never know," I say.

Hillary shakes her head. "I'll never know."

"We're like vaults," Mike says. "You can't break us."

Hillary turns to me. "So, are you going to tell your therapist?"

"Should I?"

They both shrug. Mike glances at the clock, tosses his trash into the can. Hillary and I take our last sips of tea. It's time for our next sessions. One by one, the green lights on the kitchen's master panel go on, and we file out to retrieve our patients from the waiting room.